Introducing Peace, my privacy-focused iOS 9 ad blocker

Running the Ghostery browser add-on in my Mac browsers has been illuminating:

- I can’t believe how many trackers are on popular sites.

- I can’t believe how fast the web is without them.

But that wasn’t possible on mobile, where it’s most needed… until iOS 9.

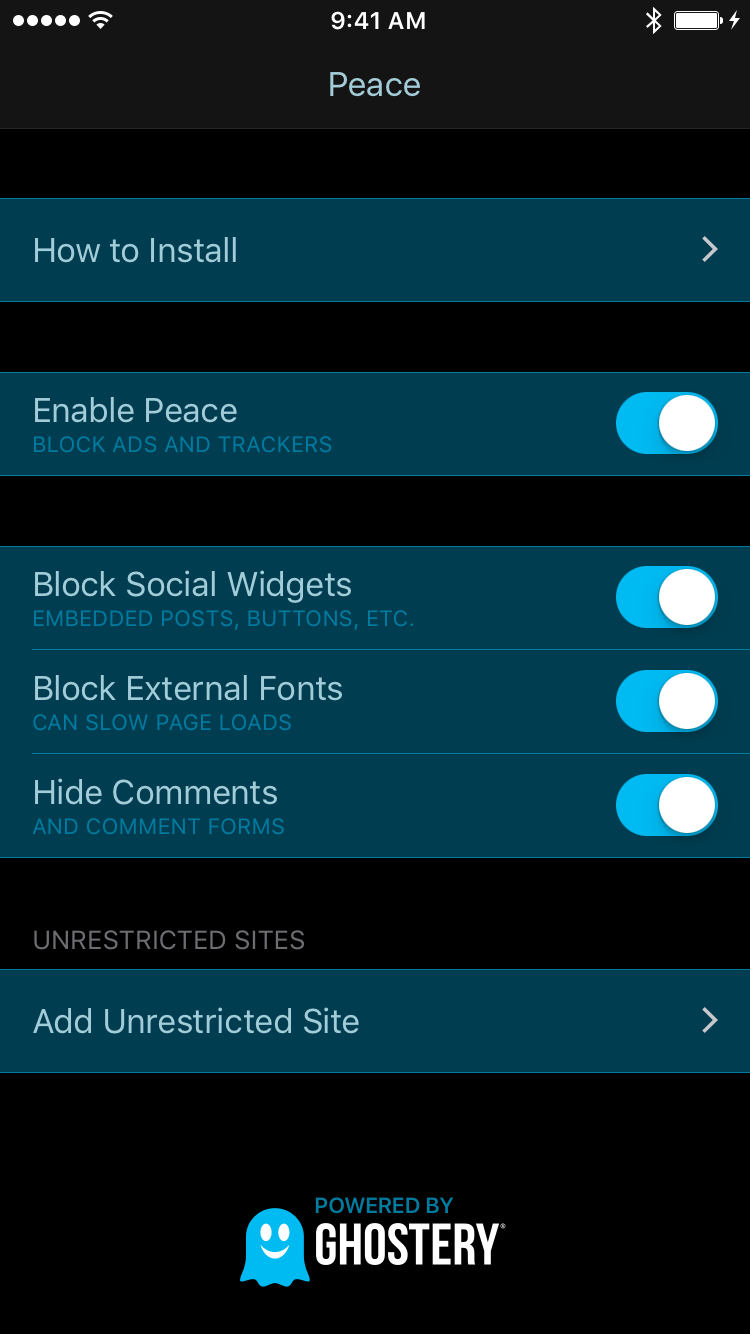

Today, I’m launching my own iOS 9 content blocker, called Peace, to bring peace, quiet, privacy, and — as a nice side benefit — ludicrous speed to iOS web browsing.

There are a lot of content blockers being released today, but Peace strikes the best balance I’ve seen between effectiveness, compatibility, simplicity, and speed, powered by what I’ve found to be the best database in the business after months of testing. And it’s just $2.99.

Why block ads?

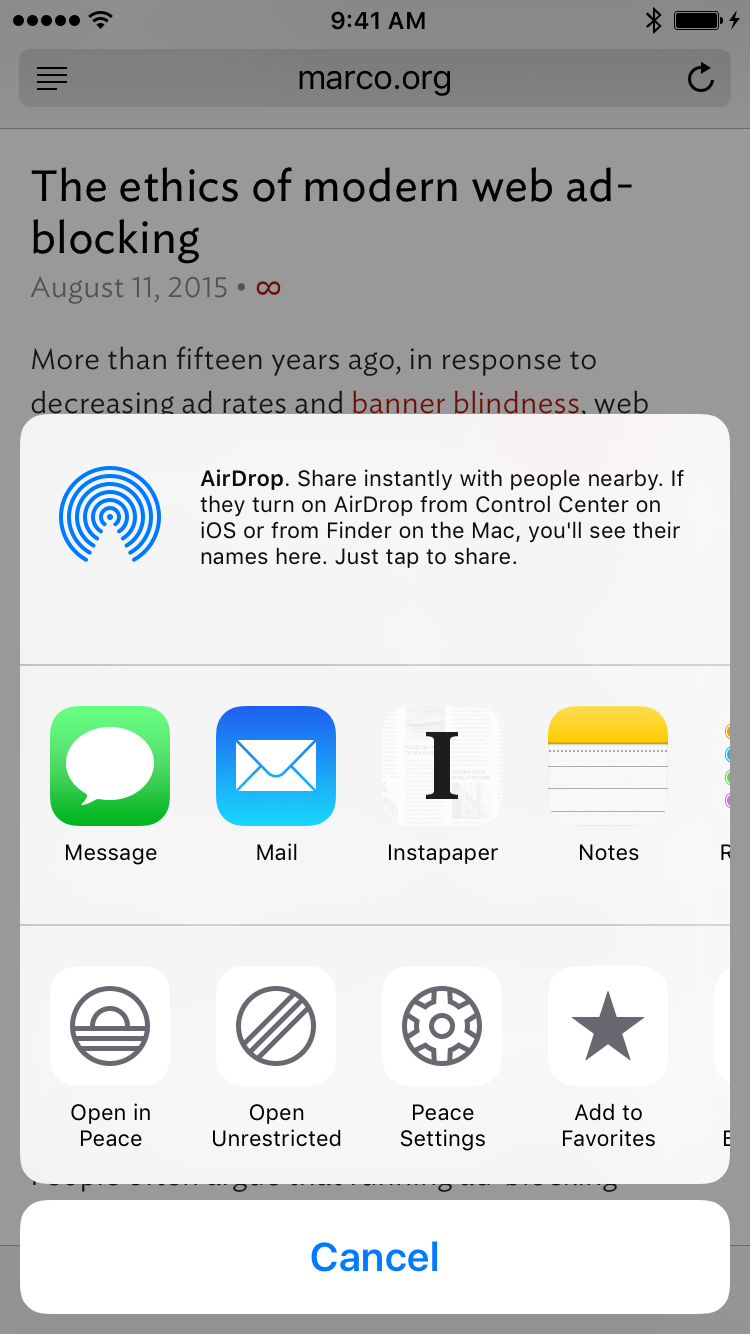

As I wrote in The ethics of modern web ad-blocking, web advertising and behavioral tracking are out of control. They’re unacceptably creepy, bloated, annoying, and insecure, and they’re getting worse at an alarming pace.

Ad and tracker abuse is much worse on mobile: ads are much larger and harder to dismiss, trackers are harder to detect, their JavaScript slows down page-loads and burns battery power, and their bloat wastes tons of cellular data. And ads are increasingly used as vectors for malware, exploits, and fraud.

Publishers won’t solve this problem: they cannot consistently enforce standards of decency and security on the ad networks that they embed in their sites. Just as browsers added pop-up blockers to protect us from that abusive annoyance, new browser-level countermeasures are needed to protect us from today’s web abuses.

And we shouldn’t feel guilty about this. The “implied contract” theory that we’ve agreed to view ads in exchange for free content is void because we can’t review the terms first — as soon as we follow a link, our browsers load, execute, transfer, and track everything embedded by the publisher. Our data, battery life, time, and privacy are taken by a blank check with no recourse. It’s like ordering from a restaurant menu with no prices, then being forced to pay whatever the restaurant demands at the end of the meal.1

If publishers want to offer free content funded by advertising, the burden is on them to choose ad content and methods that their readers will tolerate and respond to.2

Why choose Peace over any other iOS 9 content blocker?

Apple’s new WebKit Content Blocker API makes iOS ad blockers so trivial to make that there will likely be hundreds, or more, released over the next few months. Even today, on day one, there’s already tons of competition.

Today, Peace has a number of exclusive features and nice implementation details that I haven’t seen in any other iOS content blocker, but I’m sure they won’t be exclusive for long.

Making the app is easy, but creating and maintaining the database of ad and tracker URLs to block is very, very hard to do well.

Most ad blockers use public “hosts” files, advertising thousands of entries in their blocklists. I tested every hosts database I could find over the last few months, but found a number of downsides:

- They’re maintained by individuals or very small groups of volunteers, so they’re limited to only what’s encountered by a handful of people.

- They focus more on visible ads than trackers, leaving a lot of unblocked trackers flying under the radar that their maintainers don’t see.

- They can’t make exceptions for sites that break when certain ads or trackers are blocked.

- They can only block at the domain level. They can’t block only the tracking scripts on major sites, or common tracking packages that are hosted on publishers’ own domains.

- They use a lot of entries to cover all known subdomains of large ad companies, and are often filled with thousands of unnecessary entries for obsolete or very obscure ad servers.

- Using them in an iOS app usually violates their license. (A lot of people will use them anyway, but I won’t.)

Since the browser must check every resource against the blocklist as a page loads, and modern pages commonly include tens or hundreds of resources, bigger isn’t better. The bigger the list, the more time and memory necessary to enforce its rules as pages load.

Diminishing returns set in quickly: the ideal list has just enough entries to block most ads and trackers that we’ll encounter on most sites we’ll visit, but not so many that we’re burdening Safari with thousands of entries it will probably never use.

Why Ghostery?

Whenever I’d test another blocklist against Ghostery’s, I kept finding the same thing: Ghostery blocked more trackers and had fewer compatibility problems, with a reasonably sized blocklist of about 2,000 entries.

This isn’t surprising: Ghostery is a well-staffed company with much broader reach and much better tracking data than small groups of volunteers can usually achieve, with a business model that’s ethical, sustainable, and aligned with our interests.3

After being dissatisfied with every other option, only a few weeks ago, I contacted Ghostery to see if I could license their database for Peace. I thought it was a long shot, assuming that they’d either say no, or that we’d take forever to work out a deal and miss the iOS 9 launch.

To my surprise, they loved the idea and we worked out the entire deal in about a week: I’ll make and sell the app and give them a percentage of the revenue. That’s it. The app is completely my code, using a copy of Ghostery’s tracker database hosted on my server that the app periodically checks for updates.

As you can see in Peace’s privacy policy, we not only don’t collect any user data, but we can’t collect anything of much use — iOS content blockers aren’t privy to any of the user’s browsing activity. All we can do is provide a list of conditions to block. That’s it.

With Ghostery’s database, Peace is ridiculously good. This isn’t a time for me to be modest — just go try it and you’ll see for yourself.

You’ll reclaim a good deal of privacy, cellular data, and battery power, and you won’t believe how fast iOS web browsing can be.

-

I could stretch this analogy indefinitely. The menu only has brief and vague descriptions of the entrees, you’re forced to eat two pounds of bland mashed potatoes before you can enjoy your steak, the “steak” turns out to be reheated meatloaf, the waiter stops you between every few bites by shoving a different entree from a completely different restaurant in front of you and asking if you’d like to buy it as well, and glancing at these offerings automatically adds them to your bill, which turns out to be $1300 before the required 50% gratuity, and nobody told you that there were hidden cameras recording your every move for detailed analysis by fifteen creepy guys from the moment you pulled into the parking lot, even when you were picking your nose in the bathroom. ↩︎

-

Many publishers have already struck a great balance with non-abusive methods such as (clearly labeled) native in-stream ads, which don’t require cross-site tracking or abusive practices and make good money. (The saddest part about the abusive trackers and ads is that they don’t even make much money anymore. They’re abusing us for almost nothing.) ↩︎

-

Ghostery’s business model is often misunderstood. The gist of it: their browser plugin has an opt-in feature, off by default, to send Ghostery anonymous data about which third-party scripts get loaded on the pages people visit. This helps them find new trackers to block, and they offer a business version of Ghostery that big sites use to figure out which trackers people see on their sites. Third-party ad networks and analytics are so common, and their standards for embedded ads are so unenforceable (since they’re letting third parties execute arbitrary code), that web publishers need someone else — Ghostery — to tell them what’s being served on their own sites and what problems it might be causing for their visitors or potential customers. ↩︎