Originally published in The Magazine, Issue 4.

I’ve noticed a very clear trend among tech sites I read: Android fans are unusually quick to fill the comment box with rage on articles that mention anything positive about Apple or its products. The reverse — Apple fans leaving angry comments on pro-Android articles — is almost completely absent from the sites I’ve seen, including sites like The Verge that have many readers in both camps.

Recently, I wrote about a mediocre experience at a Microsoft Store and my tepid impression of the Surface, and I saw the same effect coming from die-hard Microsoft fans responding via email and Twitter: not just counterarguments, but seemingly deep-seated anger.

The anger from Microsoft and Android fans at anything pro-Apple usually has undertones of disbelief and frustration, as if to say, “I can’t believe I have to say this again. Why don’t you get it? What’s wrong with you people?”

But I never see Microsoft fans attacking Android fans, or vice versa. And the rise of anti-Apple anger has risen dramatically as Apple has been so successful in recent years.

What is it about Apple and its success that makes people so angry?

The Apple attitude

Most people don’t care about technology choices as much as we do. Maybe they’re too busy to spend more than an hour choosing a phone. Maybe they just have other things they’d rather spend time thinking about.

They perform minimal research, they’re more swayed by prices and sales, and they’re more susceptible to being railroaded by retail salespeople. They get their gadget or computer home, start using it, and suffer mild to severe irritation with it for a few years until the cycle repeats.

Most of these people aren’t posting angry comments on The Verge.

Some of them once considered an Apple product. Some of them may have even asked around about it. And some of them might have asked one of us about, for instance, the iPhone.

And we told them, “It’s great! That phone you’re using now is a piece of crap. Go out right now and get an iPhone! It’s only $200.”

Some stopped at that point, quietly put off by the suggestion that they previously made a poor buying choice, and that they can and should casually drop a significant sum of money on a nonessential gadget that may require a more expensive monthly plan than their current phone.

Some actually went out and got an iPhone. It worked out well for most of them, but some hit snags. Maybe they wanted to play videos in a format that the iPhone doesn’t support. Maybe it didn’t interact properly with their corporate email or calendar server. Maybe their old phone had an important app or feature that isn’t available on the iPhone.

Apple’s products are opinionated. They say, “We know what’s best for you. Here it is. Oh, that thing you want to do? We won’t let you do that because it would suck. Trust us. If you don’t like it, there’s the door.”

“But I need that.”

“No, you don’t. Here, try this partial workaround or alternative solution instead. It Just Works!”

“I tried that. It didn’t work.”

“…It’ll probably be fixed in the next version. Maybe it’s because of iCloud. Oh, that’s weird. I’ve never seen that before. Try clearing everything out and starting over.”

Apple’s products say “no” a lot. No, you can’t have that hardware keyboard or removable battery. No, you can’t install that app. No, you can’t have that feature.

These are usually compromises to improve the products in other ways. But if that missing app or feature is important to you, it’s easy to be put off by Apple’s refusal to deliver it, especially since it’s done in such an opinionated manner, as if to say, “Not only do we not offer that, but nobody should need that.”

As Apple has grown, so has the number of people who have fallen on the wrong end of its opinionated product design. It leaves so many markets, features, and needs unaddressed that many users are effectively forced into alternatives.

And two alternatives offer to please everyone.

The wild Northwest

Android and Windows share a common selling point: they give users and manufacturers (and, for Android, cellular carriers) much more control over their platforms and devices than Apple would ever permit. When Apple’s choices or attitude show someone the door, a buyer usually ends up here.

Microsoft also has a huge advantage with Windows: a lot of people actually need the Windows versions of the Office suite, or other Windows-only applications, to do their jobs. Boot Camp, Parallels, and Fusion are clunky, complicated,1 and expensive2 solutions for people who need to run Windows apps. Those people should usually just buy Windows PCs.

And a good portion of geeks care strongly about areas in which Apple is less “open” than its competitors. Apple’s opinionated design restricts its customers, usually because Apple believes that the result of being more permissive would be worse overall, including increased risks of security exploits, malware, and manual system maintenance. Generally, Apple tries to protect users from complexity, side effects, and technical ugliness of their choices, but they’re also always looking out for Apple’s own interests first. It’s a benevolent dictatorship.

Where Apple says “You can’t do that because we think that would suck,” Microsoft and Android usually say, “You can do whatever you want, even if it sucks.” They give users more control with endless possibilities to create problems, and it’s up to the users to tolerate or fix any resulting problems themselves. Google and Microsoft are platform libertarians: you’re generally free to do much more, but you’re on your own when it breaks.

Our technology choices reflect our values. People willing to yield some control to Apple for their needs are more likely to enjoy the benefits that Apple’s products bring by exerting that control. But people who don’t like being told what to do — people who believe they know what’s best for them, want full control over everything, and are willing to accept the resulting responsibilities — will be more comfortable with the alternatives.

The philosophical differences between these approaches, and the frequent failure to understand both viewpoints, are the roots of anti-Apple anger.

Understanding

As we see too often in politics, people fail to empathize with those with different needs or priorities than their own.

It’s much easier to get defensive and try to discredit the other side, which is at the root of “fanboy” accusations. Apple fans accuse Windows and Android users of being crass plebeians, and in turn are accused of being uncritical (“faithful”) sheep blinded by marketing and seeking status symbols.

The apparent asymmetry in angry comments is likely because the Apple-fan attitude of aloofness keeps most Apple fans away from dedicated Android and Windows sites and articles, whereas the anti-Apple attitude probably drives many people on that side to try to “rescue” or convince Apple fans that they’re blind or idiotic.

Apple’s recent success also exacerbates anti-Apple frustration. The computing industry clearly favored Windows’ libertarian-like policy for two decades as Apple languished and inexpensive Microsoft Windows PCs dominated the industry. But, in the last few years, the tides have shifted dramatically as PCs have lost some ground to Macs, and iOS and other “closed” smartphone and tablet platforms have succeeded. Nobody likes to think that their side is “losing,” especially after it was winning for so long.

But neither side is absolutely correct for everyone: just as there’s no universally correct political philosophy, users of every platform have good reasons to choose it.

The Windows and Android communities need to better understand why so many of us choose Apple, and the Apple community needs to better understand the large market of people who can’t or won’t.

◆

Last week, I wrote that I was disappointed to find so few of my recent posts with long-term, general relevance, and I was going to make an effort to increase the number of such posts in the future. So when I posted about bathroom fans and timer switches a few hours ago, I got a few responses that were mocking me for writing something seemingly frivolous after making such a proclamation.

To clarify, I only said I was going to increase the number of long-term-value posts, not that I was never going to post anything light or fun in the meantime. And I think people who complain about my seemingly frivolous subject matter probably have a different idea of “lasting value” than my interpretation.

Installing timer switches on my bathroom fans has eliminated a daily annoyance from my life. Deciding on a pillowcasing strategy has made me sleep more comfortably every night since I wrote that stupid article seven years ago. By caring about what type of headphones I use, I satisfy my own needs better and annoy the people around me less every day.

These may sound trivial, but they add up. As Joel Spolsky wrote 12 years ago:

So that’s what days were like. A bunch of tiny frustrations, and a bunch of tiny successes. But they added up. Even something which seems like a tiny, inconsequential frustration affects your mood. Your emotions don’t seem to care about the magnitude of the event, only the quality.

And I started to learn that the days when I was happiest were the days with lots of small successes and few small frustrations.

I’m constantly seeking other little ways to improve my life: ways to eliminate frustrations and create even more tiny successes and little delights every day. As I wrote four years ago:

I try to be discerning in everything, because I love it. I love the research and acquisition of specialty things, I love finding new and better versions of the things I like, and I love discovering the immense depth of hobbies and goods that most people never see.

All of these minutiae — every little thing I care about in my life, some of which I take the time to write about — adds up to a life full of little victories, and I’m extremely happy.

By sharing insights and opinions on these little things, I can make other people’s lives better, too, a little at a time.

When I first started writing, I was reaching dozens of people. Now I’m reaching hundreds of thousands, a great honor. But the far more satisfying honor is when I hear from a few of them after writing one of my life-minutiae posts, and they tell me that I’ve just made their lives a little bit better.

That’s why I do this.

If you don’t care about such minutiae, that’s fine. I just hope you have something that you do care about. But I care about this sort of thing, and I get immense joy and satisfaction from improving the minutiae in other people’s lives.

◆

I recently had a good reason to look through my blog archive for a handful of articles that were very good, relatively timeless, interesting to a broad audience, and G-rated that didn’t include any references to celebrities, political figures, or well-known trademarks. I thought I could easily come up with 5–10 suitable picks.

I found very few. And the most recent pick, the weakest by far, was almost a year old.

It was sobering.

Most of my favorite writing over the last few years was about specific products or technology companies. There’s a place for that, but in one year or three years or thirty years, who’s really going to care about the politics of technology and the nuances of gadgets in 2012?

My primary outputs, professionally, are software and writing. This is what I’m contributing to the world. None of the software I write today is likely to still be in use in thirty years, but if I write a truly great and timeless article, that could be valuable to people for much longer.

I’m going to continue to write about what’s happening in our industry. But I’m also glad that I had this chance to step back and get some perspective on my work, because I haven’t written nearly enough articles recently that I’ll be proud to show off more than a few months from now.

◆

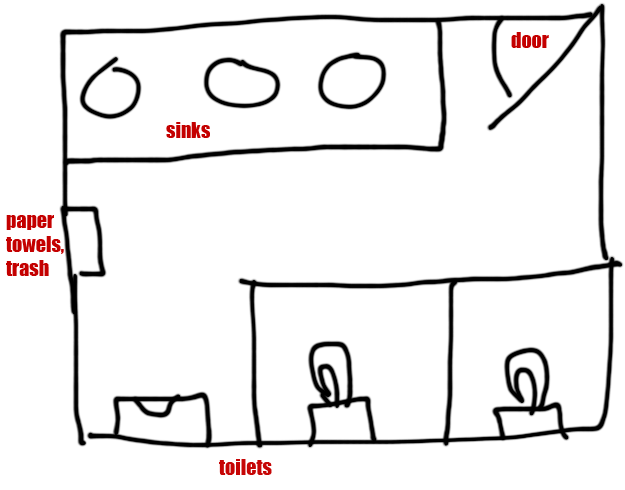

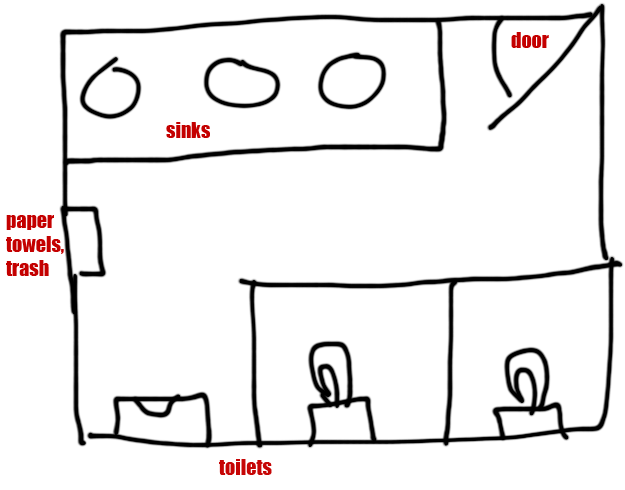

At a previous job, the shared men’s bathroom for the floor was laid out like this:

(Please excuse my drawing skills.)

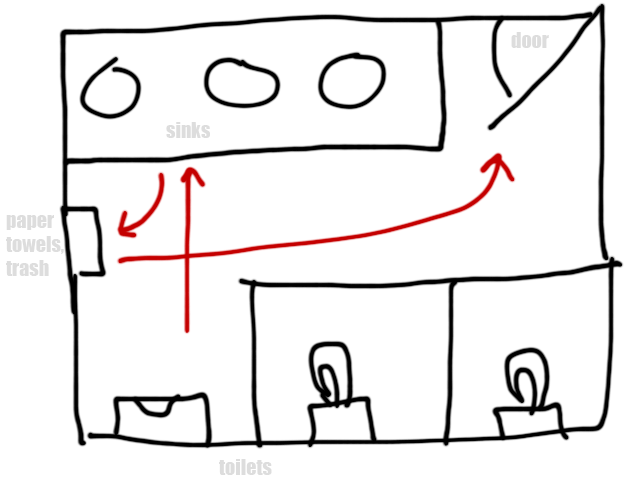

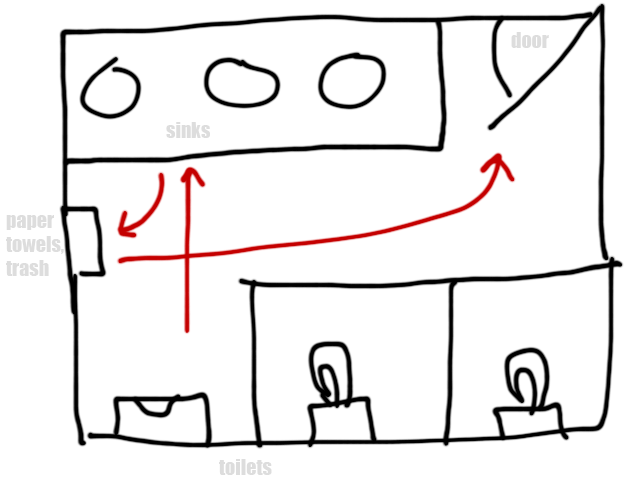

When we were done doing our business, this is the path we’d take:

Many people don’t like touching bathroom doorknobs after washing their hands. (Understandable.) But some of them dislike it so much that they’ll take their paper towel over to the door, turn the knob with it, and throw it on the floor while exiting.

By the end of the day, there would be paper towels all over the floor by the door.

One of the floor’s tenants attempted to solve this problem by posting passive-aggressive notes on the paper-towel dispenser.

The signs never worked. Instead, they just annoyed and angered people. Some people even threw more paper towels on the floor because they didn’t like the condescending way they were being instructed.

There was no chance the signs would ever work. The people who threw paper towels on the floor knew that it was “wrong”. Maybe their desire to avoid touching the doorknob was stronger than their desire to do the “right” thing every time. Or maybe they just didn’t give a damn about making the bathroom slightly worse for someone else to make it slightly better for themselves. Either way, a sign’s not going to solve the problem, because the problem isn’t that they didn’t know the right thing to do. They knew what they were doing, and for whatever reason, they didn’t care.

This problem wasn’t solved by the time I left that office. It probably still isn’t.

The pragmatic way to solve the problem would have been to adapt to what these people were going to do anyway: just put another trash can by the door.

They never tried that. They just kept posting more signs, because they were convinced that they were right.

This pattern is common. We often try to fight problems by yelling at them instead of accepting the reality of what people do, from controversial national legislation to passive-aggressive office signs. Such efforts usually fail, often with a lot of collateral damage, much like Prohibition and the ongoing “war” on “drugs”.

And, more recently (and with much less human damage), media piracy.

Big media publishers think they’re right to keep fighting piracy at any cost because they think it’s costing them a lot of potential sales.

It is, but not as many as they think, and not for the reasons they think.

The Oatmeal’s awesome comic illustrates the problem well: demand is rapidly increasing for accessing movies and TV shows outside of their traditional distribution channels, and rather than addressing this demand, the publishers are making it even harder to get their content legally in these contexts.

This is like trying to solve the paper-towel problem by moving the trash can even further away from the door.

Not all piracy represents lost sales: many pirates would never have paid, and would rather go without whatever they can’t easily pirate. That’s not a market worth worrying too much about, because there’s not much anyone can do to stop it, and any attempts to slow it down usually just limit, inconvenience, frustrate, and anger the paying customers.

But there are a lot of people who will pay to get content legally, even if it’s easy to pirate, when getting it legally is easier. (This is now the case, to a large extent, with music.)

In response to The Oatmeal’s comic, Andy Ihnatko makes a good counterargument:

The single least-attractive attribute of many of the people who download content illegally is their smug sense of entitlement. …

The world does not OWE you Season 1 of “Game Of Thrones” in the form you want it at the moment you want it at the price you want to pay for it. If it’s not available under 100% your terms, you have the free-and-clear option of not having it.

Andy’s right. But it’s not going to solve the problem.

Relying solely on yelling about what’s right isn’t a pragmatic approach for the media industry to take. And it’s not working. It’s unrealistic and naïve to expect everyone to do the “right” thing when the alternative is so much easier, faster, cheaper, and better for so many of them.

The pragmatic approach is to address the demand.

◆

Every few years, the MPAA’s lobbying power, rhetoric, and immense campaign contributions succeed in purchasing a bill in Congress to advance their agenda in a way that’s hostile to the technology industry and consumers.

Their bills have had mixed success and usually die before being brought to a vote, but SOPA and PIPA came frighteningly close to becoming law. The internet-wide protest this week seems to have stalled their progress and probably killed them for now.

But what will happen when the MPAA buys the next SOPA? We can’t protest every similar bill with the same force. Eventually, our audiences will tire of calling their senators for whatever we’re asking them to protest this time.

Eventually, we will lose.

Such ridiculous, destructive bills should never even pass committee review, but we’re not addressing the real problem: the MPAA’s buying power in Congress. This is a campaign finance problem.

We can attack this by aggressively supporting campaign finance reform to reduce the role of big money in U.S. policy. This is the goal of groups such as United Republic and Rootstrikers.

It’s also worth reconsidering our support of the MPAA. The MPAA is a hate-sink, a front to protect its members from negative PR. But unlike the similarly purposed Lodsys (and many others), it’s easy to see who the MPAA represents: Disney, Sony Pictures, Paramount, 20th Century Fox, Universal, and Warner Brothers. (Essentially, all of the major movie studios.)

The MPAA studios hate us. They hate us with region locks and unskippable screens and encryption and criminalization of fair use. They see us as stupid eyeballs with wallets, and they are entitled to a constant stream of our money. They despise us, and they certainly don’t respect us.

Yet when we watch their movies, we support them.

Even if we don’t watch their movies in a theater or buy their plastic discs of hostility, we’re still supporting them. If we watch their movies on Netflix or other flat-rate streaming or rental services, the service effectively pays them on our behalf next time they negotiate the rights or buy another disc. And if we pirate their movies, we’re contributing to the statistics that help them convince Congress that these destructive laws are necessary.

They use our support to buy these laws.

So maybe, instead of waiting for the MPAA’s next law and changing our Twitter avatars for a few days in protest, it would be more productive to significantly reduce or eliminate our support of the MPAA member companies starting today, and start supporting campaign finance reform.

◆

Why is it that your choice of smartphone platform incites so much irrational anger and so many accusations of being a “fanboy” from people who use a different one?

Normal people own, at most, one mobile phone at a time. Typically, they own the same one for 1–2 years. And smartphone owners often remain loyal to a platform for a few consecutive phone purchases. Therefore, most people can’t reasonably equivocate and get them all: they need to be decisive, and then they’re stuck with their decision for a while.

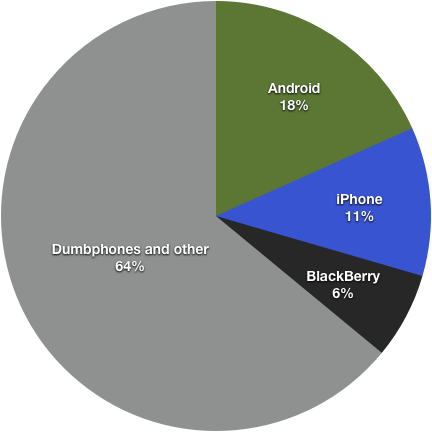

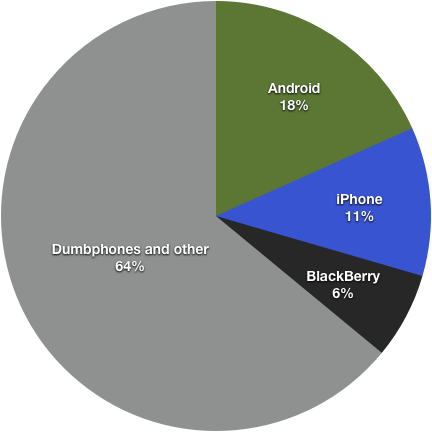

Here’s an approximate picture of today’s U.S. phone marketshare, by platform:

Source: comScore

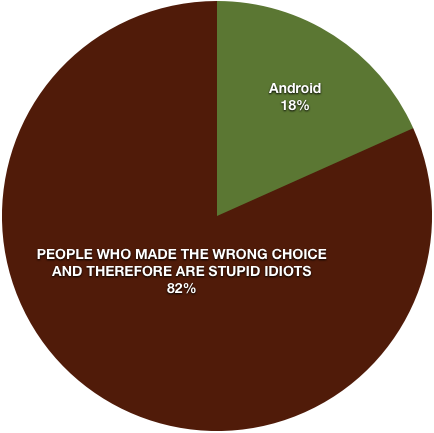

If you publicly express an opinion that any particular platform is best for a significant portion of buyers, you’re effectively saying that the people who chose differently were wrong. Most people don’t like to be wrong.

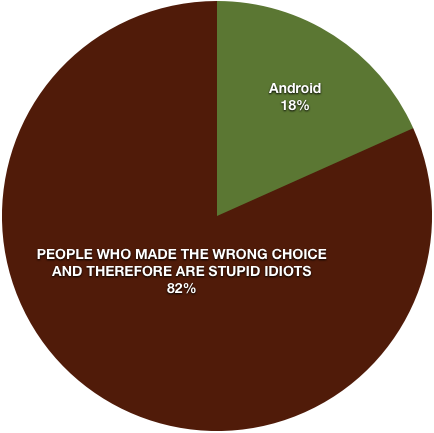

And because it’s such a massive and divided market, any stated opinion will cause this reaction from a lot of people. If, for example, you say Android is best for any common set of goals, a lot of people might get upset:

Not seeing this implication requires more open-mindedness, empathy, and attentive reading ability than many people have. So no matter how much you wrap it in qualifiers or try to be constructive, a lot of people are going to be insulted if you say something good about the thing they didn’t choose — and it’ll be even worse if you say something negative about the thing they did choose.

This is one reason why so many big publishers are so opinionless and seem to like everything. Saying you don’t like something, or that any choice is clearly the best for most people, will cause enough people to stop listening that the precious metrics that pay the bills might decrease.

When people get defensive over their choices that you inadvertently cast doubt upon, and they don’t want to admit (to themselves or anyone else) that they made the wrong decisions, they will often attempt to convince themselves (and possibly everyone else) that your opinions are invalid by discrediting you.

Hence, fanboy: a derogatory term that means someone who is blindly and irrationally devoted to a product that I believe is inferior to what I bought when faced with a similar choice, and whose opinions and arguments can therefore be completely disregarded.

I used to attempt to defend myself against accusations of being a fanboy, but I just don’t care anymore. It’s impossible to express a useful opinion to any significantly sized audience without inadvertently angering someone enough to hurl irrational insults at you.

If given the choice between expressing an opinion and being useful, or pleasing most people most of the time by saying everything is great even when it isn’t, I’ll choose expressing an opinion every time. And if that results in derogatory feedback, so be it.

◆

Apple:

- This web app or social network we’re making is going to be great.

- Our app-review rules are always in everyone’s best interests.

- Nobody wants a [popular new product category that Apple doesn’t make yet].

Google:

- Android is open.

- Don’t be evil.

- We solicit all of your personal information and track everything you do to make things better for you.

Facebook:

- Our users want to interact with brands.

- We value your privacy.

- We’re not tracking you when you’re logged out.

Everyone has their bullshit. You can simply decide whose you’re willing to tolerate.

◆

Instructions for Normal People:

- Drive somewhere and buy a cup of coffee.

Alternately:

- Wait until the electricity is restored before making coffee.

Instructions for Impatient, Geeky, Coffee Snobs:

- Light the gas stove with a match.

- Boil water in the Helvetica Kettle.

- Plug the coffee grinder into the APC UPS that still has some power left, turn it on, grind the coffee, then turn it off to conserve its power.

- Realize you had the wrong grind size, dump those grounds, fix the grind setting, turn the UPS on again, and grind the coffee properly.

- Brew with AeroPress.

Guess which method I chose.

◆

Amazon published this Kindle Fire vs. iPad 2 page shortly after its announcement on September 28, 2011. I thought it was just a temporary promo, but it turns out that Amazon is still pushing it heavily.

It’s interesting that the quotes under “What People Are Saying” aren’t linked to their sources (Gizmodo, Extreme Tech, Ars Technica, Forbes/Mobiledia). Maybe it’s because all of them are simply reactions to the Fire’s specs and price after the announcement, not reviews from anyone who actually used one. By those standards, I could have been quoted along with them that day:

“The Fire will be the first Android-powered tablet to sell in meaningful volume… It’s definitely going to compete with the iPad” — Marco.org

…but the context is far less effusive.

Why hasn’t Amazon updated the page with actual reviews since the Fire’s launch? Surely they can find some positive ones.

Anyway, the main attraction of Amazon’s Kindle Fire vs. iPad 2 page is the big comparison table. Other people’s feature-comparison checklists always leave out factors that are important to me, so I made my own additions that Amazon is welcome to include on their page:

|

|

|

|

Price

|

$199

$300 less than iPad 2

|

$499

|

|

Volume Buttons

|

No

|

Yes

|

|

Stability

|

Needs Improvement

|

Very Stable

|

|

Home Screen

|

Frustrating

That was a small swipe. Did you mean to tap? Try again

|

Easy

Tap an app to open it

|

|

Magazine Reading

|

Infuriatingly Awful

|

Pretty Good

|

|

Netflix

|

Poor

No HD, no complete full-screen viewing, poor stability, and no convenient way to adjust the volume during playback

|

Very Good

HD-quality streams, stable app, volume adjustable via convenient buttons

|

|

Available Apps

|

Not A Lot

And mostly crap

|

A Lot

Critically acclaimed apps and award-winning games

|

|

Web Browsing Speed

|

Amazon Says It’s Faster

Reviewers disagree

|

Everyone Else Says It’s Faster

They must be fanboys

|

|

Overall Speed

|

Frustratingly Sluggish

|

Very Fast

|

|

Syncing Music And Videos From Your Computer

|

Only Manually

And 6 GB is really small

|

Automatically with iTunes

16–64 GB sizes available

|

|

Available Cases And Accessories

|

Very Few

|

Tons

|

|

3G Data

|

Not Available

Isn’t everyone always on a Wi-Fi network?

|

Available

$129 extra plus $15/month for 3G service

|

|

Automatic Shutoff Feature

|

Yes

Sleeps automatically when idle or if you rest the bottom edge on a table or your pants or pretty much anything

|

Yes

Sleeps automatically when idle or when a supporting case is closed

|

|

Your Kids Can Charge Whatever They Want To Your Credit Card

|

Yes

|

Configurable

And all purchases require your password

|

|

Fun

|

Only If You Hate Life

|

Yes

|

|

Delightful

|

You Will Want To Throw It Out The Window

|

Yes

|

|

|

|

◆

In my earlier 20s when I knew everything, I was a much bigger evangelist for my technology choices. I’m accused of fanboyism a lot more these days, but only because Hacker News keeps sending huge waves of people here who tell me I’m an idiot. But I used to be much more annoying with pushing my choices onto others.

I’ve naturally reduced such evangelism as I approach 30 and realize I don’t know anything, but I’m now making a much more conscious effort to stop it.

I spent Thanksgiving weekend in my hometown and visited my friend’s parents. They used to generously pay me to fix their computer problems, but it wasn’t always productive: everything took far longer than I thought it would, and my efforts to fix one problem often created others. It was inevitable: they’re an architect and a graphic designer, and I was a computer nerd with very little professional IT experience, so I never fully appreciated the complexity of their software setups or their priorities for getting their jobs done.

My friend’s father spent this weekend battling similar issues. Having failed to set up a suitable sync system with an Android phone, he had exchanged it for an iPhone and was trying to set up iCloud and whatever software (iTunes?) syncs calendars and contacts with Outlook on Windows. It wasn’t working properly.

He’s probably not going to get it to work, and he’ll probably return the iPhone and just tolerate a lack of a synced smartphone for a few more years until he tries again with whatever shoddy pile of hacks we’ve cooked up by then to (not) sync contacts and calendars with our other piles of hacks, a simple problem that we’ve been (not) solving for decades that still isn’t reliable for everyone.

My friend told his father to dump Outlook and go all-Apple, which of course isn’t going to happen. Previously, I’d try to convince him, too. But not this time. His father has many good reasons not to switch, and I don’t understand any of them.

I said I couldn’t help him.

The iPhone and many of Apple’s products work very well for me. But for him, they don’t. It doesn’t really matter whether it’s Microsoft’s fault or Apple’s fault or iCloud flaking out or some other third-party software interacting with something somewhere. To him, the iPhone doesn’t work with his setup.

I bet very few other phones, if any, would work exactly the way he wants with no other modifications to his setup. But that also doesn’t really matter. He got a product that claimed to work in his setup, but when he tried it, it didn’t.

I choose to fit myself into most of Apple’s intended-use constraints because their products tend to work better that way, which makes my life easier. But that requires trade-offs that many people can’t or won’t make.

Previous-me tried to persuade everyone to switch to my setup, but I now know that it’s not worth the effort. I’ll never know someone else’s requirements, environment, or priorities as well as they do. I don’t know shit about Windows or Outlook or architecture.

You should use whatever works for you. And I no longer have the patience or hubris to convince you what that should be. All I can offer is one data point: what I use, and how it works for me.

◆

I bought my first iPad magazine1 last weekend: one issue of The New Yorker.

It was $4.99. Most entire apps (including mine) cost $4.99 or less, once, and this magazine is $4.99 for just one issue. Ignoring what content and apps “should” cost, and despite knowing that this is a very good magazine, this felt expensive.

As I was flipping through it, when I saw the first of many full-page ads, I was offended. I thought, “I paid good money for this and it’s full of ads?”

Consumers have tolerated double-dipping — products that cost customers money and have ads — for over a century. It doesn’t feel as offensive in contexts that have always had it, such as printed newspapers and magazines, or cable TV.

But ads shoved into a non-free iPad or web publication feel wrong to me.

I don’t regret paying for Ars Premier or Consumer Reports because I get a clean, ad-free, reader-friendly experience in exchange. But I hesitate to pay for The New York Times because I know it’s still going to be full of ads, paginated stories, and distractions.

Maybe these different standards are because the contexts are so different: magazines, newspapers, and TV all feel cheap, since they’ve shat on consumers to make a few more cents for decades, but the iPad or a well-designed website are clean, high quality, and customer-centric.

Or maybe it’s just me. I just don’t feel comfortable paying for an iPad or web publication, no matter how good it is, and then having ads shoved down my throat. It makes me feel ripped off: what did I pay for?

◆

Part of this great piece by John Gruber is about the disappointment over the new iPhone’s screen size: Apple has probably decided that the iPhone’s 3.5” screen is the right size. They aren’t keeping it “small” because they can’t make it bigger, they just don’t think it should be bigger.

It’s interesting that the expectations by the geeks and gadget bloggers this time were so heavily in favor of a larger screen, and so much of the disappointment was because we didn’t get one. I don’t remember any noticeable disappointment in previous years about it.

As a four-year iPhone user, I’ve never thought, “You know what I don’t like about this phone? The screen’s too small. I’d like to reduce my battery life, and I’d like my phone to protrude from my pocket in a larger and more conspicuous rectangle, to achieve a larger screen that I cannot comfortably use one-handed. That would be completely worth it.”

Not once.

Android phones have been one-upping each other with screen size a lot recently. It’s an interesting tactic that seems to be working, at least relative to other Android phones. When comparing phones side-by-side in a store, the larger screens really do look more appealing, and I bet a lot of people don’t consider the practical downsides.

Screen size is an easy way for the commodity hardware manufacturers to differentiate their products. This is something they know how to do: checklist spec battles. Fragmentation isn’t a concern: Android hardware specs are already extremely fragmented, and the manufacturers couldn’t care less about such costs to the ecosystem anyway.

This has caused two interesting side effects that are probably accidental but work in Android’s favor:

The gadget bloggers accustomed to reviewing seventeen Android phones and one iPhone per year are now considering screen-size increases as must-have upgrades in each new device in a series, on par with faster processors and better cameras.

Any phone update that keeps the same screen size looks old and disappointing, like keeping the same CPU for two years in a row.

- Some people who grow accustomed to large-screened Android phones are probably less likely to want to switch to an iPhone in the future, since they may view the smaller screen as a downgrade.

It’ll certainly be interesting if the latter is shown to be true in meaningful numbers.

But Android is finally getting more of its own identity. As John Gruber said in the aforelinked piece:

People who claim to be disappointed that Apple’s 2011 new iPhone doesn’t have a bigger display or LTE are effectively arguing that the iPhone should be more like Android. Whereas in truth, the iOS and Android platforms are growing more different over time, not less.

Android really is becoming much more differentiated from iOS. Flagship Android phones are looking less like iPhone knockoffs and more like, well, giant screens.

There are people who want that. But I don’t think it’s enough people that Apple should feel compelled to start competing for the largest screen size at the expense of other factors that are more important to Apple and its customers.

◆

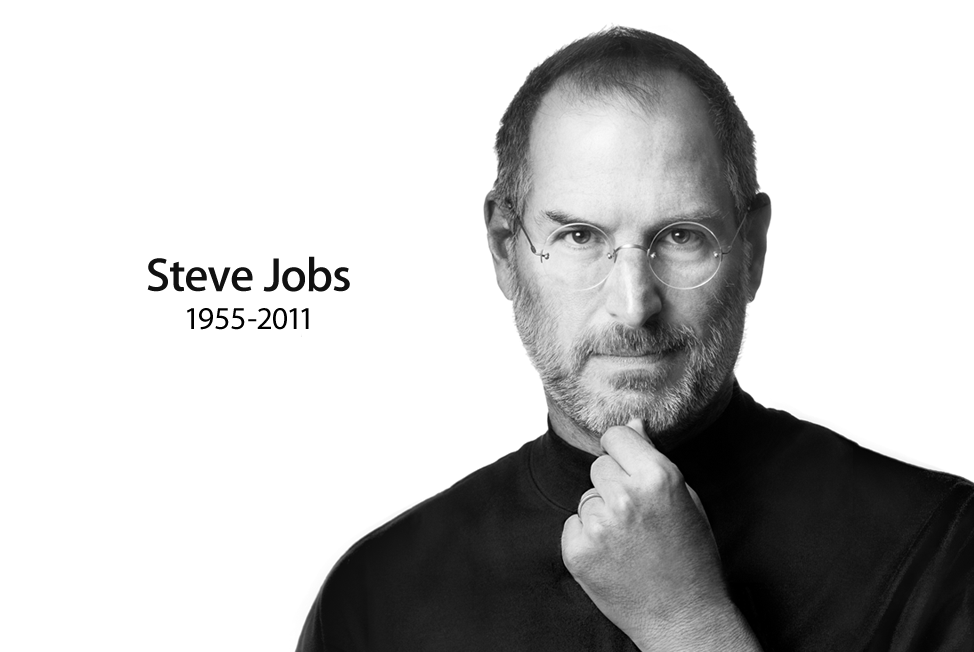

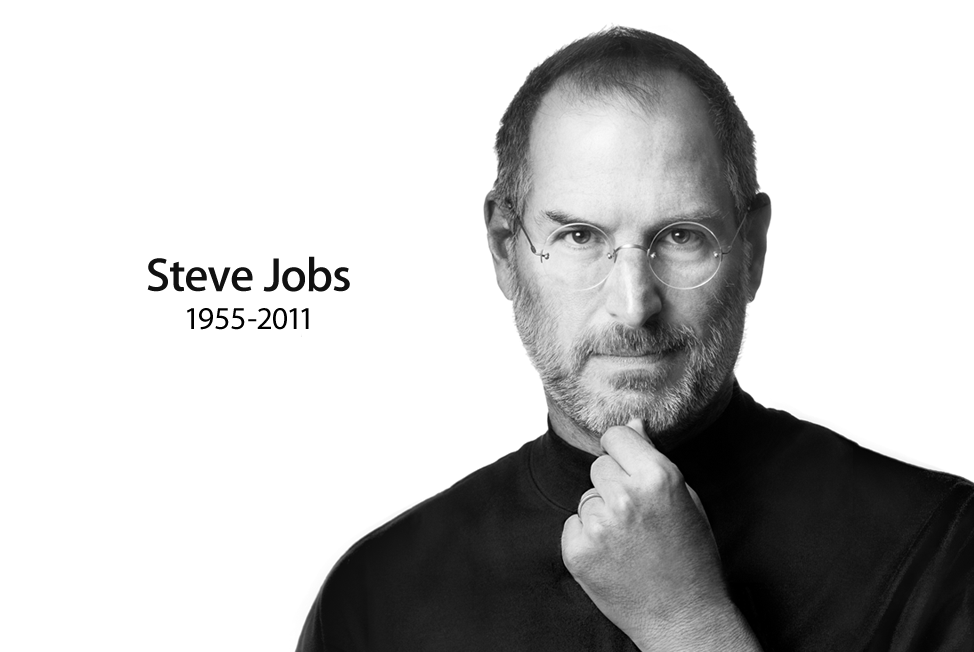

I didn’t know Steve. I never met him. I never worked for him. I never even got one of his famous one-liner email responses.

But it feels like someone close to me has died. He was so intimately involved in his company and its products (which have become critical parts of my career and hobby life), and he has publicly injected so much vision, personality, and care into our entire industry for so long, that I do feel like I knew him, even though I really didn’t.

So while I’m not qualified to write any sort of obituary, I feel moved to write this. It would be callous to keep writing about iPhone minutia without even acknowledging it.

Steve Jobs inspired generations of people to do great things. He certainly inspired me. He will be greatly missed.

I offer my most sincere condolences to his family, friends, and coworkers.

◆

This talk by John Gruber and Merlin Mann at SXSW 2009 came up again from John’s link to a fan video, and it was a great reminder to redownload the audio and listen again.

It has become much more famous than I imagine John or Merlin expected at the time, but I’m particularly fond of it because of my experience in the audience, which I should share before I become too uptight about my blog appearing unprofessional or embarrassing myself in front of my famous internet friends. I almost didn’t post this even now, and while that usually means that I really should post it, it sometimes correctly means that I shouldn’t. But oh well.

(If you don’t care about my feelings or the 5by5 crew, this will be boring. It might be as interesting as hearing about someone’s hazy recollection of a nonsensical dream. You’ve been warned.)

Tumblr sent my wife and me to Austin for SXSW 2009 to help throw a party. We flew in two hours before this talk, but it was the only thing that interested me on the entire SXSW schedule, so I rushed and made it there.

I still remember how nervous-sick my stomach felt at the restaurant with the Tumblr people beforehand. I was worried that I wouldn’t make it on time. I was going to meet these people in person whose work I admired on the internet, and I had never crossed those worlds before (and I’m not the smoothest person socially). I didn’t have my own badge and had to fraudulently use someone else’s, so I was worried about getting “caught”, whatever that would mean. I had never attended a conference before, so I had no idea how it worked, how tight security was, what it would be like inside the convention center, or where to go once I got there.

But I made it in by strategically ensuring that the badge was always flopped over or tucked under my arm slightly so nobody would notice that I wasn’t John Maloney, not realizing how lax security is at conferences (especially SXSW).

A few minutes before the talk started, I noticed that the guy sitting next to me looked a lot like Lonelysandwich. I was pretty confident that it was him — the guy’s iconic. It took my last remaining nerve to ask cautiously, “Excuse me… are you, uh, Adam?”

“Oh hey, are you Marco?”

What. How. What. (I still don’t know.)

So we got to talking, and then John and Merlin walked in to do the talk. They came by to greet Adam.

Merlin saw me and exploded with Instapaper praise. I was speechless. This guy’s a big deal on the internet, and I was worried about how awkwardly I’d introduce myself and how I’d probably put my foot in my mouth, and here he was recognizing me and introducing himself.

Meeting John was even more dumbfounding. He saw me, said nothing, and then told Adam, “Don’t let him leave.”

Tumblr was big by then and Instapaper was already more than a year old. I knew these guys knew about both, but I never expected to be personally recognized. It was an unforgettable experience already.

Then I saw the talk, during which they referenced my stuff twice. (Mind further blown.) And the talk, as we know now, was not only great but timeless and universal.

It was the first conference session I’d ever attended.

For the following year, I thought all conference sessions were that good, and I was so intimidated that I declined invitations to speak at conferences myself because I thought I had to achieve that level of quality.1

It wasn’t until I got my own badge for SXSW 2010 and attended multiple sessions there that I realized how bad most of them are, so I was finally comfortable agreeing to my first talk.2

In addition to inspiring me to be a better writer and inadvertently killing my conference-presentation confidence for a year, this famous little 2009 SXSW session leveled my juvenile notion of celebrity. After the talk, since I wasn’t allowed to leave, I was introduced to many more great people famous for their blog, software, humor, or music,3 and it went similarly well with all of them.

Among people who are well-known to subsets of internet geeks, nobody’s walking around with entourages or bodyguards. Nobody’s forced to wear hats and sunglasses outside or avoid shopping in public because they’ll get mobbed with fans and paparazzi. In the wise words of Ted Dziuba, “We all recognize that it’s just the internet. At the end of the day you still go outside and nobody knows who you are.”

The internet “celebrities” I was so nervous to meet are now my friends. I see them a few times each year at conferences. It turns out that we’re all just regular people who like similar things and are in the same little circle of interest.

So next time you’re at a geeky conference and have an opportunity to meet someone whose work you admire, just go up and introduce yourself, because they’re just a regular person, they never get “recognized” during the other 360 days each year, and they’ll probably really appreciate it.

And you should really listen to that talk.

◆

With so many projects, if the customer is willing to go without a small subset of the functionality they think they need, it can save a massive amount of effort, cost, and complexity and result in a much more elegant, hassle-free solution that makes them much happier in the long run.

This option isn’t always feasible. Sometimes, “needs” really are needs. But often, people’s “needs” are much more flexible than they think.

Apple’s customers are often the sort of people willing to make these tradeoffs, because that’s how most of Apple’s products are designed: if you can compromise on some of the features and capabilities you think you need, you can get a product that works better and makes you happier with far less aggravation. And for most people, the benefits will outweigh the missing features.

This culture of compromise has been cultivated by Apple’s relentless pace of forcing progress and killing legacy support. Apple’s implicit message is simple: “We know what’s best. If you do things our way, everything will work very well and you’ll be happy. If you don’t like it, that’s fine with us.”

People who aren’t willing or able to compromise on their needs regularly are much more likely to be Windows customers. The Windows message is much more palatable to corporate buyers, committees, middlemen, and people who don’t like to be told what’s best for them: “You can do whatever you want, and we’ll attempt to glue it together. It won’t always work very well, and you might not like the results, but we will do exactly what you asked for.”

For many (or even most) of Apple’s products, the forced compromises are critical to their greatness. There’s no way to achieve delightful, well-designed, deeply integrated platforms with highly polished software and very few problems, but that are also generous with access rights, open to deep modification by middlemen or end users, and able to run on a large, diverse, and unregulated pool of hardware.

For Windows 8 to succeed, especially for its tablets to compete well against the iPad, it will need to adopt a more Apple-like confidence to say “no” to its customers when they ask for everything under the sun. And, surprisingly, they might be doing exactly that.

One of the reasons Metro is interesting to people like me who usually ignore Microsoft is that it’s full of very un-Microsoft-like decisions, generally for the better.

The question isn’t whether Metro will be good: it probably will be. And that’s a huge accomplishment for Microsoft that they should be commended for.

But how will their customers react?

Will Metro be meaningfully adopted by PC users? Or will it be a layer that most users disable immediately or use briefly and then forget about, like Mac OS X’s Dashboard, in which case they’ll deride the Metro-only tablets as “useless” and keep using Windows like they always have?

How will Windows developers react to the restrictive Metro environment after being able to do almost whatever they wanted for nearly two decades?

And how well will the many groups within Microsoft, a company famous for infighting, adopt a fundamental shift toward simplicity and restraint when so many of them seem to be going in the other direction?

◆

Ben Brooks noticed and blogged about how Instapaper’s social features, introduced earlier this year, are minimal:

There’s just a list of articles that people you chose to follow decided that they liked. All without knowing who, or if, anybody will ever see that they liked that article.

It’s a fascinatingly private social system.

That was exactly the idea, and I’m very happy to see it perceived that way.

Social features are tricky. Social dynamics in real life are complex, so every social mechanic we construct or word choice we make will carry unintended baggage, connotations, and ambiguities. (“Like”. “Friend”. “Follower”.)

Social networks also need to address difficult issues with identity, privacy, harassment, spam, and information overload.

These systems require a lot of time and money to develop, maintain, and support. And when they’re ready, they need to compete with all of the other social networks for people’s time and attention.

With Instapaper’s following system, I wanted to deal with as little of the difficult baggage as possible, even if it meant omitting some of the “sticky” social dynamics that can significantly boost user counts and engagement. The result is a very small social feature-set that piggybacks on other established social networks: Twitter, Facebook, and email.

There are no public usernames, avatars, or profile pages. Nobody’s quitting Facebook for Instapaper. Companies aren’t rushing to establish an Instapaper following. No newly engaged couples have rushed to update their statuses on Instapaper.

To label each story in the interface with the person it came from, Instapaper just uses the label from however you found them. If you found me by searching people you follow on Twitter, I’ll be “marcoarment”. If you found me through Facebook, I’ll be “Marco Arment”. And if you found me by email address, I’ll be “me@marco.org”. Instapaper could cross-reference these, but it doesn’t.1

There are no notifications whatsoever for following and unfollowing. Nobody can tell who follows them, how many people do, or even if anyone does. In addition to removing the emotional rollercoaster of follower counts and unfollows, this may actually increase following activity: if people realize that others won’t know when they follow or unfollow, they may feel more comfortable doing so. (I sure do.)

In short, I want to leave the social features to the social networks. I want to use them to make Instapaper better, not try to make Instapaper replace them. They can deal with all of the baggage and reap all of the rewards. I’m not interested in that game.

Instapaper takes advantage of your social networks to let you easily share what you’re reading and give you recommendations when you want them (and only then), but remains a quiet escape from the social networks when you just want to read.

◆

Jacqui Cheng at Ars Technica wrote an article on why RSS is bad for you:

The first time I went without RSS in August, I simply went around to three or so of what I consider to be the best sites to get the latest news from. I combined that with my usual e-mail communications … and my regular scans of Twitter in order to figure out what was going on during the day. It was stress-free, and I never felt like I was missing anything—I knew that if something truly important or controversial blew up, I’d hear about it instantly via Twitter and our loyal readers.

The next day when I loaded up my feeds, there were literally thousands of items piled up from the day before. … And when I ended up sifting through them all, I realized that I hadn’t missed a single story doing things the “old fashioned” way—rather, by following all these feeds, I was instead seeing hundreds of iterations on the same handful of stories. And I was wasting time going through them all day long.

RSS is a great tool that’s very easy to misuse. And if you’re subscribing to any feeds that post more than about 10 items per day, you’re probably misusing it. I don’t mean that you’re using it in a way it wasn’t intended — rather, you’re using it in a way that’s not good for you.1

You should be able to go on a disconnected vacation for three days, come back, and be able to skim most of your RSS-item titles reasonably without just giving up and marking all as read. You shouldn’t come back to hundreds or thousands of unread articles.

What Jacqui did in RSS’ absence is always helpful: letting other people filter popular news sites for you. This is critical to sane RSS usage so you don’t need to subscribe to the frontpage feeds of high-volume blogs (Engadget, Lifehacker), aggregators (Reddit, Hacker News), or general news sites (The New York Times, CNN). If you like those sites, either browse them “manually” without RSS whenever you feel like it, or just wait for people to link to it from Twitter, Tumblr, Facebook, or Google’s social network of the year. And let this role inform your following decisions on these networks.

But if that’s the only way you get your news, you’ll only ever see the most popular articles. If you’re trying to get away from the “echo chamber”, that’s going to make your problem worse.

RSS is best for following a large number of infrequently updated sites: sites that you’d never remember to check every day because they only post occasionally, and that your social-network friends won’t reliably find or link to.

I currently subscribe to 100 feeds. This morning, I woke up to 6 unread items: one each from 6 of my feeds. Granted, it’s a Sunday on a holiday weekend, so this is a pretty low-activity day. On high-activity days, I usually wake up to about 25 items.

I don’t use an RSS app on the desktop anymore: I just use the Google Reader site. I can check it whenever I want, but nothing’s in my Dock collecting red badges to distract me every few minutes.2

This setup works well. I can follow tons of low-traffic sites and keep my reading list more diverse than if I relied only on social links, but other people ensure that I never miss anything great on the high-volume sites.

◆

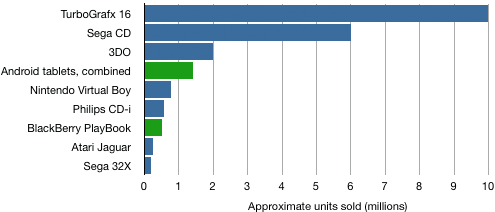

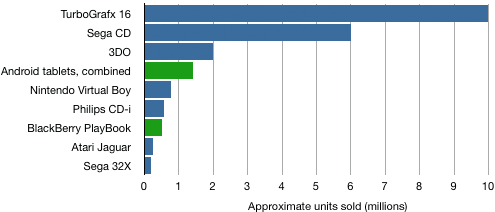

HP hasn’t released any sales figures for the TouchPad yet. I wonder if it will outsell the Virtual Boy this year.

I didn’t include the iPad’s approximately 30 million units on here because it distorted the graph’s scale too much.

(source, source, source)

◆

I’m not a patent lawyer. I’m not even a lawyer. I’m just a software developer, and like every software developer, I’ve probably unknowingly infringed upon hundreds of patents while routinely doing my job.

In my efforts to educate myself on the patent system, I’ve learned about the requirements for getting a patent, and what sorts of ideas are patentable. One of these requirements is novelty:

An invention is not patentable if the claimed subject matter was disclosed before the date of filing, or before the date of priority if a priority is claimed, of the patent application.

A patent must also not be obvious to a person of ordinary skill in the field that the patent pertains:

A patent may not be obtained though the invention … if the differences between the subject matter sought to be patented and the prior art are such that the subject matter as a whole would have been obvious at the time the invention was made to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which said subject matter pertains.

But as we’ve seen, time and time again, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office enforces these (and other) rules extremely poorly, resulting in thousands of patents being issued that most people knowledgeable in their field would immediately recognize as invalid.

And that’s not new. Bogus patents have been issued for decades.

The USPTO has repeatedly shown that they cannot and will not do their job to prevent most invalid patents from being granted. In the field of software, their negligence seems especially egregious.

With the rise of patent litigation due in no small part to the “we don’t sue people” Intellectual Ventures and their shell companies (that only sue people), the number of patent applications is likely to increase dramatically over time. If the USPTO is granting bogus patents because they’re just slipping past overworked patent examiners, it’s only going to get worse.

Invalid patents aren’t just funny government slip-ups. (“Oh look, someone patented toast and linked lists! Stupid patent office!”)

Since the economics of civil lawsuits, especially patent lawsuits, prevent most cases against small defendants from ever getting near a court, the potential cost to society of issuing an invalid patent is massive.

If someone threatens your small business with a patent lawsuit, it doesn’t matter whether the patent is valid. Because for you to prove that it’s invalid would take far more time and money than you probably have. The only sensible course of action, the path taken by almost everyone threatened by patent litigation, is to settle with the patent-holder as quickly as possible for whatever amount of money they demand.

In practice, therefore, an issued patent is a valid patent as long as the patent-holder doesn’t try to sue anyone too large. (And even the largest corporations usually settle.)

That’s the problem.

The patent system is a good idea, in theory.

The patent rules are sensible and should prevent highly damaging patents from being issued, in theory.

The patent office should make every reasonable effort to ensure that they enforce the rules, in theory.

But in practice, this isn’t what happens. It’s not even close.

Good public policy isn’t based on what should be, but what is.

Patents are a good idea. The rules of the patent system were well-designed and have been refined for hundreds of years, mostly for the better. But if they’re not going to be properly enforced, it’s hard to argue that the system is anything but fundamentally broken. And if the rules can’t be properly and consistently enforced, I don’t see how it can be fixed.

◆

This paragraph in Marshall Kirkpatrick’s Why I’ll Never Redirect my Personal Blog to Google Plus scared me a bit:

Google Plus doesn’t have RSS feeds, or email subscription options. Both are important to me; I want to speak to my readers however they want to be spoken to. Some day, we’ll be able to write to and read from any platform in any other platform, just like we can call one phone network from inside another phone network now.

I hope he’s being clever here, because we had that. (And I think we still have it.)

It’s interesting that so much online publishing is moving into a small handful of massive, closed, proprietary networks after being so distributed and diverse during the big boom of blogs and RSS almost a decade ago.

In many ways, we’re better off now: publishing online is far easier, less time-consuming, and more accessible than it has ever been, which has brought content, voices, and consumers online that wouldn’t have been otherwise.

But all of these proprietary networks that want to own and hold in your content are reversing much of the web’s progress in some other areas, such as the durability and quality of online identity.

If you care about your online presence, you must own it. I do, and that’s why my email address has always been at my own domain, not the domain of any employer or webmail service.

You might think your @gmail.com address will be fine indefinitely, but if I used a webmail address from the best webmail provider at the time I broke away from my university address and formed my own identity, it would have ended in @hotmail.com. And that wasn’t very long ago.

I’ve always built my personal blog’s content and reputation at its own domain, completely under my control, despite being hosted on many different platforms and serving different roles over the years. It has never been a subdomain of any particular publishing platform or host.

Tumblr respects this. From day one, David and I gave it free custom-domain support, full HTML control, and no forced branding or advertising. But Tumblr is a hybrid of a blog-publishing platform and a social network that seems truly unique — the “pure” social networks aren’t nearly as willing to allow you to own your identity there.

Locking your identity in won’t prevent a major social service from succeeding. Sadly, most people don’t care about giving control of their online identity to current or future advertising companies.

But there will always be the open web for the geeks, the misfits, the eccentrics, the control freaks, and any other term we can think of to proudly express our healthy skepticism of giving up too much control over what really should be ours.

◆