https://marco.org/2009/10/01/via-doodlepipski-innocentdestruction-modern

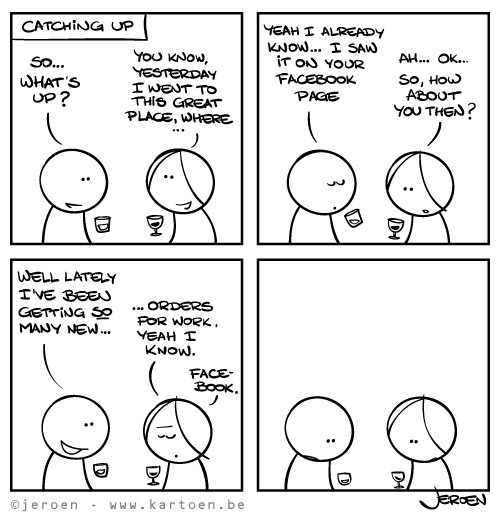

(via doodlepipski, innocentdestruction)

Modern interaction.

I’m Marco Arment: a programmer, writer, podcaster, geek, and coffee enthusiast.

https://marco.org/2009/10/01/via-doodlepipski-innocentdestruction-modern

(via doodlepipski, innocentdestruction)

Modern interaction.

https://marco.org/2009/10/01/and-yet-this-principle-is-built-into-the-very

And yet this principle is built into the very structure of the things they teach you to write in high school. The topic sentence is your thesis, chosen in advance, the supporting paragraphs the blows you strike in the conflict, and the conclusion— uh, what is the conclusion? I was never sure about that in high school. It seemed as if we were just supposed to restate what we said in the first paragraph, but in different enough words that no one could tell. Why bother?

— Paul Graham: The Age of the Essay

The Democratic Party: Depressingly Ineffective.™

The Democratic Party: We Won’t Put Up Much Of A Fight.™

The Democratic Party: Wait, We Won?™

The Democratic Party: We’ll Forgive Our Opponents Repeatedly So You Don’t Have To.™

The Democratic Party: Defeat You Can Believe In.™

The Democratic Party: How Much More Of A Majority And Public Support Do We Need To Get Anything Done?™

https://marco.org/2009/10/01/when-people-talk-about-search-being-a-great

When people talk about search being a great business model (for, say, Twitter), they should distinguish between search with puchasing intent, which is an incredible business model, and search without purchasing intent, which is a terrible one.

— Chris Dixon: Online advertising is all about purchasing intent

https://marco.org/2009/10/02/cd-makin-i-think-im-in-love-with-your-new

“I think I’m in love… with your new CD recorder.”

Walt Mossberg likes the HTC Hero and calls it “a worthy competitor to the iPhone, the BlackBerry and the Pre”.

John Gruber points out:

Thank goodness they boogered up the front display with big “HTC” and “Sprint” logos. It retails for $280 but there’s a $100 mail-in rebate, and only ships with 2 GB of built-in storage. That compares really poorly to the $99 no-rebate-necessary 8 GB iPhone.

It doesn’t sound like a “worthy competitor to the iPhone” so far. Let’s see what else Mossberg had to say about the Hero:

…after a year, Android has less than 10% of the 85,000 apps the iPhone now offers.

…the Hero’s price is a bit deceptive.

The Hero’s hardware isn’t especially beautiful. It’s a dull grey, noticeably thicker than the iPhone, with a smaller screen and six buttons plus a trackball…

It comes with just two gigabytes of memory…

One big drawback is battery life.

I sometimes found the touch screen unresponsive, requiring multiple pokes at an icon.

It sounds like the Hero is a decent phone when compared to other Android phones, but I’m not seeing how this effectively competes with the iPhone. How many iPhone owners or holdouts are going to consider an alternative that costs more, has worse battery life and less storage, is thicker and uglier, doesn’t work very well, and also doesn’t have a physical keyboard?

By what standards is this a “worthy competitor”? And what would the tech press say if the next iPhone was uglier, cost more with a deceptive rebate arrangement, and had a flaky touch screen?

https://marco.org/2009/10/03/opacity-the-first-vector-graphics-editor-that-i

Opacity: the first vector-graphics editor that I was able to figure out how to use. I occasionally need to make a quick icon for web or iPhone use, and this is a great tool for that.

Thanks, John.

https://marco.org/2009/10/04/now-that-the-medium-is-evaporating-publishers

Now that the medium is evaporating, publishers have nothing left to sell. Some seem to think they’re going to sell content—that they were always in the content business, really. But they weren’t, and it’s unclear whether anyone could be.

https://marco.org/2009/10/04/anyone-who-can-lay-out-an-iphone-along-with-its

Anyone who can lay out an iPhone along with its recent competitors (never mind those previous generations of lame “iPhone-Killers” they presented in 2007 and again in 2008) and say with a straight face that the only advantage Apple has is its ability to make things look nice should be in politics (perhaps AM Radio), not blogging about technology.

This article is so poorly copy-edited that I think I might be the only person who has read it. But it makes some great points.

https://marco.org/2009/10/05/how-long-before-people-live-in-loft-apartments

How long before people live in ‘loft apartments’ inside old box stores?

— Zach Klein (via Scott Heiferman)

https://marco.org/2009/10/05/adobe-can-barely-write-objective-c-apps

Adobe can barely write Objective-C apps themselves. We’re still waiting for an update to CS4 that makes it not crash when you move the mouse too fast. You really want to trust them to manage your memory, translate your code and keep up with Apple’s SDK? Let me know how that works out for you.

— Jeff Rock: On Authoring iPhone Apps via Flash CS5 (Chartier beat me to quoting it)

https://marco.org/2009/10/05/perhaps-googles-stiffest-competition-in-the

Perhaps Google’s stiffest competition in the immediate future isn’t Bing and Yahoo, but rather it’s the likes of Wikipedia, Twitter, and Facebook. Just as we no longer search for the news (24 of the top 25 newspapers have shown record declines in circulation), in the future we will no longer search for products and services; rather they will find us via social media.

— Is Google a Social Media Company? (via Fred Wilson, Bijan Sabet)

I hope not. That sounds awful.

Fortunately, I think this is one of those new-media thought extrapolations where we’re so far into the clouds that we can’t even see reality anymore.

I’m sure products and services (or “brands”, as they like to call themselves) will continue trying to find us on social networks. That doesn’t mean that we’ll welcome them in many contexts. People are already annoyed that they can’t rant about their local cable monopoly’s awful service on Twitter without receiving a cheerful but useless reply from a PR drone with the frustratingly false implication they can do something to improve their employer’s mediocrity.

When you tell your friends that you’re having coffee at Aroma, the last thing you want is to get an at-reply from Starbucks asking you to try their location across the street. When you congratulate your friends for their new baby on Facebook, you don’t want Pampers to auto-message you (or them) about the great features on their new diapers.

Meanwhile, if you search Google for coffee or baby announcements, the chances are much better that you’re interested in seeing commercial offers — or at least won’t be interrupted and offended by them.

Social media, by design, resides in a similar context as socializing in real life. “Brands” can’t interrupt us in the social context without being awkward and unwanted. Imagine the mood if your new father-in-law followed your grandfather’s war story during Thanksgiving dinner with a pitch for his Amway energy drinks and a great investment opportunity for everyone at the table.

Commercial interaction just doesn’t work in that context, and I doubt that it ever could.

https://marco.org/2009/10/05/one-reason-i-really-like-the-idea-of-give-me

One reason I really like the idea of Give Me Something To Read (and the execution, but I’m a little biased there) is because of how rote the web has become for people like us — geeks with a thirst for information: we set up massive incoming torrents and feeds and dashboards of content, and then make it a race to read it all (and complain and brag when we can’t).

— nostrich on Give Me Something To Read, Instapaper’s companion site that he edits incredibly well.

https://marco.org/2009/10/05/adams-ode-to-his-favorite-computer-speakers

Adam’s ode to his favorite computer speakers inspired me to finally post a photo of my new desk setup.

My first computer speakers were the pack-ins that came with my first sound-card kit. They were powered by a pair of C batteries each, and didn’t sound awful. (I’ve heard much worse from computer speakers.)

But they sucked compared to the midrange consumer stereo I had a few feet away from the computer, so I, a geeky sixth-grader, got my mother to drive me to Radio Shack so I could buy the 1/8”-to-RCA cable that would connect my sound card to my stereo.

I never bought computer speakers again.

Sure, they can be compact, practical, and economical. But I’ve never heard a set of computer speakers that I liked better than a decent detachable-speaker integrated stereo or, like my current setup, a basic receiver and a pair of bookshelf speakers.

Computer speakers tend to fail in four main ways:

My current setup follows a pretty simple formula: Get whatever receiver you can find for a reasonable price that’s from a decent consumer brand. Mine’s an Onkyo TX-8222. Stereo only, no surround nonsense. Old technology works just fine here: garage sales, thrift stores, or your parents’ basement will often have perfectly good receivers for free or almost-free.

Then get a really great pair of bookshelf speakers. These can often be almost-free as well, but I decided to splurge and get the “entry-level” (cheapest) pair available from a highly regarded audiophile brand (these). They cost about $250. Nearly every highly-regarded speaker brand has a great bookshelf offering for less than $300. Audiophiles hold their equipment to such high standards (that frequently cross the placebo line in hilarious and sad ways) that even their “entry-level” models sound a lot better than nearly anything you’ll find in Best Buy, even for far more money.

Then set the equalizer (and any applicable bass/treble knobs) to flat, unmodified output.

It sounds ridiculously good.

And you don’t need a boomy subwoofer to annoy your neighbors and distort your sound mix. (I know, they make good foot rests. Get a UPS instead.)

$250 plus the cost of the receiver ($0-200) is a lot of money compared to most “premium” computer speakers, which tend to be $150-300. But how often do you need to buy these? Bookshelf speakers and basic receivers can last decades.

Computer speakers still win if you need a complete setup for very little money, or if you need them to take up as little space as possible. But the massive difference in sound quality makes the receiver setup far more worthwhile to me.

Note: I recognize that my speakers should be on stands that raise them by about a foot. I haven’t yet found good stands of the proper height. They still sound amazing.

https://marco.org/2009/10/06/other-than-poor-performance-memory-consumption

Other than poor performance, memory consumption, and crashiness, though, Flash is well-regarded.

https://marco.org/2009/10/06/this-is-the-brand-new-windows-mobile-6-5-the

This is the brand new Windows Mobile 6.5. (The painful review.)

“Microsoft My Phone” sounds like a prank you’d pull on your friends.

https://marco.org/2009/10/06/san-francisco-is-also-perhaps-infamously-an

San Francisco is also, perhaps infamously, an intellectual and cultural bubble in which ludicrous ideas can find support, particularly in the tech industry. Before long, you may find yourself nodding in sincere agreement as someone explains the inane first-world problem that their startup or pet open source project is trying to solve. It’s hard work to maintain perspective and not get caught up in a way of thinking that privileges the desires of young white men with high technical proficiency and lots of disposable income. But then, this is a double-edge sword: some ideas that seem silly at the outset have world-changing, democratizing potential (I’d like to think Twitter is one such idea, of course). Be open, but skeptical.

What Verizon delivers with their Android phones will definitively indicate whether there’s any chance of a Verizon iPhone for the foreseeable future.

My guess: there isn’t, and the Verizon Android phones will have Verizon’s proprietary content stores spewed all over them with at least one major Android feature locked down or removed at Verizon’s request to preserve their nickel-and-diming model.

I bet Apple did go to them this past spring to attempt to get a Verizon iPhone off the ground, and I bet Apple’s reps left the discussions, thinking, “These guys are nuts.”

But Verizon knows what it wants, and it it definitely doesn’t want to be in the situation AT&T is in today with iPhone owners: reduced to a dumb pipe with very little device branding, no lock-in, no customer loyalty, little to no revenue share from phone-based content sales, and only negative press resulting from the relationship.

As just a few examples of the inherent incompatibility that probably exists between Apple and Verizon, you can bet your ass that Verizon would want some significant concessions:

That’s all assuming, of course, that Verizon hasn’t made any “progress” since their dark days of stripping Bluetooth functionality from Motorola’s flip phones.

But I don’t see any signs whatsoever that anything has changed. Their new “choose our network first, then settle on whichever phone sucks the least” ad campaign sends a clear message: We know we have the best network, we don’t care about devices, and we’re doing just fine this way.

https://marco.org/2009/10/08/with-windows-7-pc-users-will-at-last-have-a

With Windows 7, PC users will at last have a strong, modern successor to the sturdy and familiar, but aged, Windows XP, which is still the most popular version of Windows, despite having come out in 2001. … While XP works well for many people, it is relatively weak in areas such as security, networking and other features more important today than when XP was designed around 1999.

— Walt Mossberg: A Windows to Help You Forget

Think about that for a minute.

Windows is the most popular desktop operating system by a long shot, and Windows XP, most of which was designed and written ten years ago, is the most popular version. In other words, most computer users are running 10-year-old technology.

To most computer users, overall industry progress has seemed stagnant for nearly a decade. It’s as if the majority of computer users in 2000 were using Windows 3.0.

Way to go, Microsoft.

The rest of this review is odd. Mossberg says OS X’s advantage over Windows is “no longer true”, the comparison has become a “toss up”, and “Apple will have to scramble” to become better than Windows again. But then, after praising a few shallow features, he mentions many massive shortcomings and headaches. It sounds like Windows 7 is a lot better than Windows XP (which, based on my brief time using it in VMware, seems accurate), but is still in a different league from OS X in many important areas. Has Mossberg always been the king of trumpeting diminished expectations, or is this a new thing? Is Microsoft a major Wall Street Journal advertiser?

https://marco.org/2009/10/08/nvidia-will-postpone-further-chipset-investments

GPU giant NVIDIA has confirmed that the company is putting the brakes on the Nforce chipset line because of legal wranglings with Intel.

If this is accurate, this could seriously impact the notebook market for a while.

NVIDIA makes today’s best mobile chipsets. Apple’s entire notebook lineup currently uses them because they deliver much better integrated graphics performance with the 9400M than Intel’s pathetic GMA line. The most recent generation is also extremely power-efficient, which played a significant role in the Mac laptops’ recent increases in battery life.

It’s an annoying problem for Apple short-term if NVIDIA suddenly exits the chipset market. (It’s a much bigger problem if they stop manufacturing their current lineup altogether, but that’s unlikely — they’ll probably just stop developing new generations until this is sorted out.)

But it’s a much bigger problem for NVIDIA. There’s not much money to be made at the high end because it’s a miniscule market. The real money is in the massive low-end and mobile markets — the markets that Intel has been trying to strong-arm themselves into for years and slowly succeeding, despite having truly awful integrated GPUs, because hardly any computer users ever need the power of even the cheapest discrete GPUs.

If Intel succeeds in suing NVIDIA out of the integrated-graphics and mobile chipset markets, I’m not sure how long NVIDIA can stay in business.

Ged Maheux of the Iconfactory recently wrote Losing iReligion, in which he criticizes the business prospects of the App Store. He cites some general concerns, but much of the post is based on the unfortunate commercial failure of their Ramp Champ game.

By Ged’s account, Ramp Champ was developed with a sizable budget and marketing push (not relative to most games, but relative to most iPhone apps):

When the Iconfactory & DS Media Labs released our latest iPhone game, Ramp Champ, we knew that we had to try and maximize exposure of the application at launch. We poured hundreds of hours into the game’s development and pulled out all the stops to not only make it beautiful and fun, but also something Apple would be proud to feature in the App Store. We designed an attractive website for the game, showed it to as many high-profile bloggers as we could prior to launch and made sure in-app purchases were compelling and affordable.

Subjectively, I remember seeing massive build-up for it from the people I follow online. It was clearly a major effort. But it has apparently failed:

The lack of store front exposure combined with a sporadic 3G crashing bug conspired to keep Ramp Champ down for the count.

… Ramp Champ’s sales have not lived up to expectations for either the Iconfactory or DS Media Labs. What’s worse, many of the future plans for the game (network play, online score boards, frequent add-on pack releases) are all in jeopardy because of the simple fact that Ramp Champ hasn’t returned on its investment.

Its sales could have been disappointing for any number of reasons. Maybe people just didn’t like the gameplay, which presents carnival Skee-Ball-style ball-rolling, target-knocking-down action with extremely strong, detailed graphics and atmosphere. But, as Ged points out, Freeverse’s Skee-Ball has been successful, and it’s a very similar type of game.

Simplistic gameplay doesn’t prevent iPhone games from being successful — in fact, it usually helps. One of the most popular recent games is Paper Toss, a game so simple and mindless that watching someone play it on the subway made me lose much faith in humanity.

What happened? As usual, I have a theory: there are two App Stores.

App Store A: Simple, shallow games and apps with mass-market appeal. These live and die by the App Store’s “Top” lists, so success is difficult to achieve and is short-lived at best, but with the largest potential payoff for the lucky few at the top. These apps are developed quickly and cheaply, and are rarely updated once their initial popularity (if any) dies down. Very few are priced above $0.99. Impulse-buying is king, with most purchases happening on the phone itself, and most buyers don’t know or cares whether you’re an established developer unless your name begins with “MLB”. Nearly every best-selling app falls into this category.

App Store B: Apps and games with more complexity and depth, narrower appeal, longer development cycles, and developer maintenance over the long term. These tend to get little attention from the “Top” lists, instead relying on the much-lower-volume App Store features (e.g. “Staff Picks”), blogs, reviews, and word of mouth. More of their customers notice and demand great design and polish. More sales come from people who have heard of your product first and seek it out by name. Many of these apps are priced above $0.99. These are unlikely to have giant bursts of sales, and hardly any will come close to matching the revenue of the high-profile success stories, but they have a much greater chance of building sustained, long-term income. Due to the likely lower revenue cap, these are usually developed on small budgets by individuals who can do most or all of the work themselves.

These two stores exist in completely different ecosystems with completely different requirements, priorities, and best practices.

But they’re not two different stores (“Are you getting it?”). There’s just one App Store at a casual glance, but if you misunderstand which of these segments you’re targeting, you’ll have a very hard time getting anywhere.

The Iconfactory seems entirely set up for producing excellent apps for App Store B. Their most well-known app, Twitterrific, is solidly in that camp. The problem with Ramp Champ is that they targeted App Store A in gameplay depth and type (which may not have been intentional), and budgeted for App Store A’s expected sales for a hit. But they built, designed, and promoted it as if they were targeting App Store B.

Freeverse’s Skee-Ball game targeted App Store A, but in a way that’s more likely to appeal to its more simplistic, impulse-oriented demands, starting with the name and icon:

Skee-Ball is a registered trademark that the Iconfactory didn’t license (Freeverse did), so the Iconfactory couldn’t call theirs by that name, make the game look anything like it, or even mention it anywhere in the description. But that’s how most people know this sort of game.

App Store A’s customers don’t read our blogs. They don’t see the professional reviews. They also don’t see the Staff Picks section in the store because it’s not in the phone version. Your only chance to get these customers is with the “Top” and category lists, so you need to get them quickly and efficiently. When they breezed past “Ramp Champ” in the low-information list view, they probably couldn’t tell what it was.

The primary screenshots of each game also show a clear difference for people who did select either app for more information:

Skee-Ball is immediately recognizable, well-known, and obvious. But Ramp Champ looks likely to lose out on nearly every impulse purchase from people who don’t want to spend much time looking into it — which is nearly every buyer for App Store A.

The Iconfactory’s apps are able to compete strongly when people choose apps based on research, reviews, or feature comparisons. But that’s not how App Store A’s customers operate. Whether Ramp Champ is a better game than Skee-Ball is irrelevant to them because they’ll never take the time to find out.

Many of Ged’s complaints — in fact, many of everyone’s complaints relating to App Store economics, promotion, and ranking — only apply to App Store A. He’s right to condemn the practical economics of it and question whether to invest significant resources into it again.

But App Store B is doing fine. It’s remarkably stable. This is the store I live in with Instapaper and happily share with many extremely talented developers, including Loren, James, Adam and Cameron, Jeff and Garrett, and — unquestionably — the Iconfactory.

We enjoy great advantages by targeting App Store B:

There are also, of course, some disadvantages:

Personally, I would never trade this for the hit-driven, high-risk, quick-flip requirements of the mass market, even if it means that I’ll never be profiled in Newsweek for making hundreds of thousands of dollars in a few months with the App Store.

https://marco.org/2009/10/13/toothpaste-for-dinner-interview-cheat-code-i

Toothpaste For Dinner: interview cheat code

I wonder how many people actually know (no cheating with internet searches) what game that code was for and what it did.

https://marco.org/2009/10/13/the-problem-with-seo-is-that-the-good-advice-is

The problem with SEO is that the good advice is obvious, the rest doesn’t work, and it’s poisoning the web.

https://marco.org/2009/10/15/a-multigrain-bagel-toasted-with-light-butter

I don’t eat “light” or “diet” products, generally — if something’s bad for me, I just eat less of it. As far as I can tell, the bagel shop doesn’t actually have a substance called “light butter”. But their default butter allocation is ridiculous, so when I order, I ask for a small amount. I’ve tried various phrases:

But these either get ignored, resulting in oversaturation, or translated when repeated back to me as “with light butter”. The only reliable way to ensure a small amount of butter is to specifically ask for “light butter”.

The inaccuracy of that phrase really bothers me.

(Next week’s rant: The nonstandard naming of the “multigrain” bagel. Or is it “seven-grain” today? “Whole wheat”? No, that’s something different in most places. I just want the one with the oats on the outside.)

(via Casey Liss)

However, I won’t be buying an R8 any time soon, and neither should you. Because I’ve been down the supercar road three times now, with a Ferrari 355, a Lamborghini Gallardo and a Ford GT. And I can assure you it’s not lined with girls and jelly. It’s mostly a forest of pot holes, expense, frustration, terror and dirty trousers.

(He doesn’t use the serial comma because he’s British. How quaint.)

https://marco.org/2009/10/15/in-app-purchase-now-available-for-free-apps

From Apple, via a developer mass-mail:

Now you can use In App Purchase in your free apps to sell content, subscriptions, and digital services.

You can also simplify your development by creating a single version of your app that uses In App Purchase to unlock additional functionality, eliminating the need to create Lite versions of your app. Using In App Purchase in your app can also help combat some of the problems of software piracy by allowing you to verify In App Purchases.

This could be a big deal if it’s adopted by developers in meaningful volume.

Why now? Apple’s previous reasoning for disallowing this, “free apps should remain free”, still applies just as much as it did yesterday. What was the motivating factor for this change?

My guess is that this is a big response to the $0.99-app problem. (It’s also worth noting that, as far as I know, this is the first time Apple has acknowledged app piracy as a problem.)

For new apps, there’s now little reason to make separate free and paid versions — it now makes sense in many cases to have what I’ll call a “free+” app until someone else thinks of a better shorthand term: free for a limited or ad-supported version, with in-app purchase for premium features or content. But this doesn’t completely solve the separate-app problem for everyone:

And it raises other questions:

But, if “free+” pricing takes off, it could have a number of positive effects:

There’s no question that this is a great move for both users and developers.

https://marco.org/2009/10/16/i-just-cant-bring-myself-to-say-freemium

I just can’t bring myself to say “freemium”.

https://marco.org/2009/10/16/the-lesson-of-the-sidekick-failure

Earlier this week, all data stored on T-Mobile Sidekick devices, including contacts, calendars, messages, and photos, had almost certainly been lost in a major infrastructure disaster by Microsoft. Fortunately, Microsoft is now claiming that “most, if not all” of the user data will be restored. But the Sidekick products and T-Mobile have suffered irreparable reputation damage.

It’s easy to jump on Microsoft about this, but I can’t fault them entirely. They absolutely should have had offline, offsite backups. But major outages and data loss happen all the time. Our industry is based on incredibly complex and interwoven systems that shuffle massive amounts of data around, frequently hitting physical and practical storage, bandwidth, and performance limits that need to be worked around in ways that necessarily add complexity, dependencies, and potential failure scenarios.

The real problem is the Sidekick’s design, as I learned from TidBITS’ take on the disaster:

Unlike many smartphones, Danger-based phones store data in a cloud - servers located hither and yon that you don’t manage, but are imagined to be universally and continuously accessible. These phones retrieve information as necessary and cache a temporary copy on the phone, a copy that’s not intended to be a permanent set of stored records. The data also isn’t intended to be synced to a computer as with a BlackBerry, iPhone, Android, or other smartphone, but accessed via a Web site or a phone.

It sounds more like the Sidekick data lives on something akin to an IMAP server: you can have some local copies, but the server is master. With IMAP, the copies persist even after a computer or phone restarts, of course, just as you might expect. But in the Danger approach, locally cached data is erased on restart or if the battery runs out of power.

This design, not a failed SAN upgrade with no backups, is the most severe flaw and most negligent mistake here. It didn’t technically cause the Sidekick disaster, but it dramatically increased its severity from an inconvenient service outage to a complete loss of all customers’ data.

The “cloud” — hosted, centrally-managed services — cannot be your only copy of data. Just as RAID is not its own backup, cloud services are not inherently backed up, although they usually make every effort to maintain data integrity and regular backups. But even when done well, that only accommodates for a subset of loss scenarios. For example, if someone gains access to your account and “legitimately” (as far as the service is concerned) deletes your data, or a botched sync operation unhelpfully synchronizes a mass deletion across all sync clients, cloud infrastructure probably can’t help you. Even if they have offline backups, the chances of them accessing them just to get your old files from an isolated incident are slim.

You aren’t in control of your data if you can’t easily and frequently make useful backups onto your own computer and your own media.

I recognize that it’s hypocritical for me to say this as the lead developer of Tumblr, which does not yet offer an automated feature for users to download backups of their blog content. So I took some time this week and started to write one. I’m happy to announce that Tumblr will be releasing an easy backup tool in the coming weeks. (I will also make an easy backup feature for Instapaper shortly.)

All of my blog’s content, with images, is less than 200 MB. A list of my entire Instapaper reading history is less than 1 MB. The sum of my contacts and calendar data, synced by MobileMe, is probably less than 5 MB. That’s nothing, and given how much time I’ve put into the creation of all of this data, and that it would only consume a third of a $0.26 Taiyo Yuden CD-R (or less than 5% of a $0.45 TY DVD+R), it’s embarrassing that offline backups onto my own media haven’t become routine.

So I’m hereby starting the trend of backing up my hosted data just as carefully, completely, and frequently as my local files. I know this won’t spread to most people, because most people don’t care. But I certainly do, and if you’ve made it this far into this post, you probably do, too.

If my data suddenly and permanently disappears from a hosted service, it should only be an inconvenience, not a loss.

Brunch.

https://marco.org/2009/10/19/kids-can-do-detailed-technical-things-and-they

Kids can do detailed, technical things, and they can do them well. Have you seen them on skateboards and surfing? It doesn’t have to be a BMX, it can be a pot and a pan and a knife, but we wrap them up in cotton wool and treat them like babies and they’re not.

https://marco.org/2009/10/19/belief-in-conspiracy-theories-can-be-comforting

Belief in conspiracy theories can be comforting. If everything that goes wrong is the fault of a secret cabal, that relieves you of the tedious necessity of trying to understand how a complex world really works. And you can feel smug that you are smart enough to “see through” the official version of events.

— The Economist in a great article on political craziness.

From John Gruber’s article about Windows 7 adoption:

The truth is that no one really knows why Vista fared so poorly in the market. It defies a simple explanation.

I’ll try to provide one: Most people had no reason to upgrade, and plenty of reasons not to. I’d guess that Gruber’s theory stated earlier in the article is spot on:

What if the reason why most PCs are still running XP has nothing to do with whether Vista is “good” or “bad”, but rather is the result of indifference on the part of whoever owns these untold millions of XP machines, be they at home or in a corporate IT environment. I.e., that switching to Vista, regardless of Vista’s merits, seemed like too much work and too much new stuff to learn; that the nature of the PC as a universal commodity is such that most of them belong to people who value “old and familiar” more than “new and improved but therefore different”.

I think this explains Vista’s poor adoption, but as part of a much bigger problem: the lack of a reason for regular people to ever upgrade to any new OS release.

Our industry has collectively taught average people over the last few decades that computers should be feared and are always a single misstep from breaking. We’ve trained them to expect the working state to be fragile and temporary, and experience from previous upgrades has convinced them that they shouldn’t mess with anything if it works. They’ve learned to ignore our pressures to always get the latest versions of everything because our upgrades frequently break their software and workflow. They expect unreliable functionality, shoddy software workmanship, unnecessary complexity, broken promises from software marketers, and degrading hostility from their office’s IT staff.

When we tell them that the new OS is faster and better, only to have the upgrade break a piece of software that we don’t care about but they really do, we burn our likelihood that they’ll ever willingly upgrade again. Every time we tell them that they can now easily edit video or make DVDs, only to have them abandon their first effort in frustration and never attempt it again because our software sucks, we drive them closer to indifference or resentment toward future technology.

So when our nontechnical aunts refuse to upgrade from their Pentium III PCs with Windows 98 that work well enough for them and are set up exactly how they prefer, we have nobody to blame but ourselves.

The upgrade market for average PC owners is dead. We killed it.

It was never very strong to begin with, because most people don’t know or care about OS updates, as Gruber pointed out. They get the new OS whenever they buy their next computer, because we don’t give them a choice.

What’s driving computer sales? Well, in the ’80s and ’90s, we were making huge hardware advances that affected a large portion of normal people. Every few years, people needed to upgrade their computers for a new killer app or a massively improved generation of their existing apps.

But the rate of such changes that are relevant to average people has plummeted in the last decade. Graphical interfaces, multitasking, SimCity, porn, email, shopping, and dating sold a lot more new computers than nearly anything we’ve come up with since 2000 except malware. (I honestly believe that malware carried computer sales for most of the last decade. That only worked because we’ve taught people, with a combination of misinformation and omission, two great lies: that computers slow down over time, and that the only way to fix a malware infestation is to buy a new computer.)

Hardware, software, and the internet have all reached mature plateaus of dramatically slowed innovation. In 1998, when everyone was happily using long filenames and browsing the internet and playing their first MP3s and editing their first scanned photos to email to their relatives, a five-year-old computer couldn’t easily do any of these things.

But what common tasks in 2009 can’t be accomplished by a 2.8 GHz Pentium 4 PC with Windows XP SP2 and a cable internet connection — the average technology of 2004? Not much that regular people actually do.

We’re still burning their trust, time, and money, but we’re offering much less in return. It shouldn’t surprise any of us that they stopped caring.

https://marco.org/2009/10/19/verizons-new-ad-idont-well-now-its

Verizon’s new ad: iDon’t.

Well, now it’s definite: there won’t be a Verizon iPhone for a long time, if ever. Verizon is clearly investing heavily in Android instead, presumably because they can exert much more control over the software and devices for their own promotional, branding, and add-on revenue priorities.

Indeed, nothing has changed at Verizon.

I’m interested to see how much more “open” their Droid™ devices are than the iPhone. Verizon’s known for being open, permissive, and developer-friendly, right?

What if Apple entered a massive iPhone partnership with Sprint, possibly by purchasing a significant slice of it?

Sprint has a great U.S. data network and desperately needs hot devices that can bring an influx of new customers. Sprint isn’t worth much and could really use some cash.

Apple has hot devices that deliver tons of new customers to their carriers, but desperately needs a great U.S. data network. Apple is worth a lot and is sitting on an assload of cash.

https://marco.org/2009/10/19/grubers-special-brand-of-whoopass-opened-up-on

Gruber’s special brand of whoopass, opened up on Dan Lyons. (Again.)

Sidenote: In searching for the canonical spelling of “whoopass”, I found this. (My initial guess at the spelling, “whupass”, is not an acceptable variant.)

https://marco.org/2009/10/20/dan-meths-latest-video-is-great-google-street

Dan Meth’s latest video is great:

Google Street View Guys

A new College Humor cartoon! Ever wonder what it’s like for the dudes who have to drive those Google camera cars around? I think it’s a little something like this…

The creative background, explained in this follow-up, is very well done.

https://marco.org/2009/10/20/how-is-it-that-everything-about-microsofts

How is it that everything about Microsoft’s business is backward looking? This is the real problem they have now. They’re fighting wars that are already over. They’re investing huge energy into defending things they already control, like Windows. As they do this, as they put so much effort into lost causes like search (Bing v. Google) they keep missing out on new things. So their problems just keep getting bigger and bigger, like a snowball rolling down a hill.

https://marco.org/2009/10/20/a-curious-sidenote-on-apples-impressive-updates

A curious sidenote on Apple’s impressive updates today:

The 27” iMac’s base configuration is $1699. It has a 2560x1440 resolution and can be used as a standalone monitor from another computer. It’s a new LED-backlit IPS panel likely to have an excellent color gamut, contrast ratio, and pixel response time.

The 30” Cinema Display is $1799. It has a 2560x1600 resolution. It’s an older CCFL-backlit panel with mediocre specifications.

https://marco.org/2009/10/22/steven-frank-is-as-good-at-titles-as-i-am

One section about App Store economics:

Specifically, you have a large group of people who will download and suffer any old shit by the bucketload as long as it is free or extremely cheap. And you have 10% of people who are actually particular about software quality and are willing to pay for it.

In other words, you have the Windows market, and the Mac market, but within the app store itself. And you’d better be damn sure which one you’re targeting, and set pricing and development schedule accordingly.

One of many great points densely packed into this post.

https://marco.org/2009/10/22/barnes-noble-announced-the-nook-yesterday-as-a

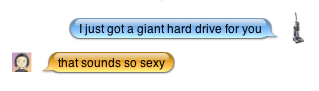

Barnes & Noble announced the Nook yesterday, as a clear competitor to (and, in many ways, a blatant ripoff of) the Kindle. Notably, the reading area is still e-ink, but they replaced the keyboard area with a traditional backlit, touch-screen LCD. The idea is that the LCD can do the quick animation and touch controls that e-ink can’t do well, and the e-ink can do the readable text that LCDs can’t do well.

Geeks are thrilled about its hardware. But I have some doubts about some of the practicalities of its design.

The brightness of the LCD will be distracting when reading the e-ink screen. There’s been no mention of an ambient light sensor for dynamic brightness, so I assume it doesn’t have one, which means it’ll blind you at night or be too dim in the sun without constant adjustments.

Presumably, the LCD is frequently turned off during reading to reduce distraction and conserve battery power, but it will be jarring every time it turns on.

Having two adjacent screens will create navigational confusion. A lot of people will try to touch the e-ink display out of confusion, a bad guess, or ingrained habit and be slightly frustrated every time. Displaying some interactive elements on the e-ink screen, including dialogs and input boxes, adds to the confusion. It’s a touch-screen device, but only in one area. You touch the things that you interact with, except those.

The book-lending feature is The Social. How many Nook owners are likely to know any others? It’s a nice feature, but it’s not one that they should spend much time marketing.

And while I’m all for fair marketplace competition, it’s misleading to include Project Gutenberg in advertised catalog numbers. The same sentiment applies to Google, Sony, and others who do this in any implied comparison to the Kindle’s catalog. Technically, yes, those are ebooks, but everyone has access to them and hardly anyone wants to read them. I recognize that this is a nitpick, but in a market this young, it’s important that consumers aren’t misled. (They’re already going to be upset when they realize that Amazon’s and B&N’s respective devices can’t read the other’s books.)

I’m hoping for more competition in the ebook-reader market, so the Nook’s introduction is great news. But I’m skeptical enough about it that I strongly recommend that you wait until the reviews come out, and you use one in person at their stores (a huge advantage over the Kindle), before making any buying decisions.

https://marco.org/2009/10/23/ive-been-using-iphone-mms-effectively

I’ve been using iPhone MMS effectively.

https://marco.org/2009/10/23/coding-horror-treating-user-myopia

(via Gruber — I swear we have separate sites, really)

The plain fact is users will not read anything you put on the screen.

This is one of the many reasons why Windows 7 is so mediocre. The interface is smothered with explanatory text. (Was Vista as bad in that regard? I never used it.)

Microsoft’s typical response to bad designs is to add text to explain them. Then, when that doesn’t work, add a text-heavy dialog box to ensure that the user noticed the other text. (I will never stop laughing at that dialog.)

https://marco.org/2009/10/24/all-computers-in-the-store-come-with-support-and

All computers in the store come with support and Microsoft Signature; a free service that removes all the “free” antivirus and other PC manufacturer software that crufts up a new PC, and gives customers a pristine installation of Windows 7.

— Microsoft Store Mimics, and Enhances, the Apple Store Experience

This tidbit about the (creepy) Microsoft Stores is interesting. Microsoft’s direct entry into retail is already going to strain a lot of their existing retail and OEM relationships. This is only going to exacerbate the problem. And it sends a terrible message to people: “Our PCs are great, but not the way all of our OEM partners sell them.”

The most significant side of Microsoft’s retail stores, though, is general PC support. I’m curious to see how this plays out. To what extent will they offer PC support? What if you didn’t buy the PC from a Microsoft Store? What if it’s one of the same models that the Microsoft Store sells, but you got it from Costco or the manufacturer’s website? What if you built your PC yourself from parts? Will support ever cost money, and if so, how much, and under what conditions? If it will be mostly free or cheap, what’s stopping Microsoft Stores from becoming overwhelming zoos of people waiting on line to plunk down their crapbooks with malware infestations? And if a lot of people go to the Microsoft Store for support, how will this affect the retail partners, such as Best Buy, who make a lot of money performing PC support services today?

(And what’s the point of the Microsoft Surface? I saw one in an upscale office’s lobby. I tried to use it, but its touch-screen driver had crashed. Really. There was an obtuse dialog on screen about it, but I couldn’t dismiss it, because touches weren’t being intercepted as mouse clicks. The receptionist didn’t notice. I think I was the only one to look at the $10,000 table that day. Across the room was a tremendous rear-projection touch-wall displaying a 9-foot-tall Internet Explorer window and an on-screen keyboard. Despite the keys being nearly a square foot each, touch-detection accuracy was so poor and registered incorrect keys so frequently that we couldn’t successfully type “tumblr.com” before we were called into the office.)

https://marco.org/2009/10/25/the-more-i-think-and-learn-about-the-curious

The more I think and learn about the curious pricing of the 27” iMac, the more bizarre and incredible it seems.

It has a resolution of 2560x1440, which no other monitor in the industry seems to have (that I can find). 30” LCDs are the same width but 1600 tall. Shrinking 2560-wide into a screen that’s 3” smaller diagonally yields an impressive pixel density, especially given the panel’s still-immense size.

It has an IPS panel. IPS is the best and most expensive LCD type, giving the best viewing angle and the least color- and brightness-shifting as the angle increases in any direction. Nearly every panel on the market, including every laptop panel, is the cheap TN type. (TN panels wash out as soon as you move your head slightly, especially vertically, which is why it’s so hard to find a good viewing angle for your laptop lid while watching a dark movie.) Other 27” TN panels exist (only at the lower 1920x1080 resolution), but I can’t find any other 27” IPS panels.

It’s also LED-backlit.

So it’s a very high-specced, brand new panel that’s apparently not being mass-produced yet (since no other monitors for sale are using it). That must be expensive. How much of the base 27” iMac’s $1700 retail cost does this represent?

The closest existing panel for comparison, spec-wise, is the 30” IPS panel that Apple uses in their Cinema Display. It has the ultra-high resolution and size, but doesn’t compete with the 27” iMac’s panel for brightness, contrast, power efficiency, or color range. It’s overpriced by today’s standards at $1800, but not by much — Dell’s original 30” monitor with the same panel is $1200, and a newer version with better specs (although still not as good as the new iMac’s) is $1700.

A standalone monitor with the new iMac’s panel would be perfectly reasonably priced at about $1500. From Dell. Apple’s only charging $200 more than that for theirs, and there’s an entire high-end computer stuck to the back of it.

When they mentioned on last week’s quarterly earnings call that they expected lower profit margins for a new product, I don’t think anyone expected a change of this magnitude. How are they making anything — or even not losing money — with the base-model 27” iMac?

My guess: a massively successful negotiation with the panel’s manufacturer (most likely LG) to get not only an incredible price on these panels, but also apparent exclusivity for a while. It’s a hell of an accomplishment, and presumably a hell of an effort, for a computer that isn’t Apple’s most-selling model (or even product line). That raises a more interesting question: Why?

Until we know why the panel is so cheap, I bet we’re going to see a lot of Mac Pro owners buying 27” monitors for $1700 and trying to figure out what to do with the free computer stuck to the back. For new-computer shopping, a lot of people are going to abandon whichever laptop or Mac Pro they were considering and get this instead.

That helps answer the “why” question: Maybe Apple wants to push more buyers away from today’s default system-type choice — laptops — and show them why they should consider getting a fast, spacious desktop instead. And, for the time being, it’s a desktop with absolutely no equivalent in the PC world.

https://marco.org/2009/10/25/i-love-the-random-emails-i-get-by-having-a

I love the random emails I get by having a catch-all.

https://marco.org/2009/10/26/todays-xkcd-geocities-tribute-redesign-is

Today’s xkcd Geocities-tribute redesign is historically accurate down to the smallest details.

https://marco.org/2009/10/26/i-really-like-jim-cloudmans-response-to-my-imac

I really like Jim Cloudman’s response to my iMac article. And that’s a great theme.

My unexpectedly popular iMac post has been linked by a lot of people in the tech community, some with very large readerships, and is one of my most-viewed posts already.

To date, it has received about 20% fewer views than the reverse trick-or-treat quote, which I neither wrote nor discovered, because the quote has received gobs of referrals from StumbleUpon.

Marc and Clint are defending ebook readers from the categorical criticism and doubt in blogs over the last few days, sparked by remarks by John Gruber and Jason Kottke.

I got a Kindle 2 in February, mostly so I could make Instapaper work well on it. I expected it to be used mostly as a development device that I would occasionally use to read a book.

The following week, Tiff was packing lightly for air travel, and I made her take the Kindle instead of a handful of books. She thought it was weird and unnecessary, but she semi-reluctantly tried it for the trip.

I just got it back a few weeks ago.

Tiff plowed through more than 20 books on the Kindle. At one point in the middle, she read a book on paper (because it wasn’t available on the Kindle) and absolutely hated it. Her commentary was priceless: she couldn’t easily look up word definitions, she couldn’t change the font size, it was awkward and lopsided to hold near the beginning and end, and it would lose her place if she fell asleep while reading.

Most people won’t instantly jump to buy ebook readers after seeing them in TV commercials or liveblogged keynotes. They need to be experienced in person. (The ability to do this easily will give Barnes & Noble a huge advantage over Amazon.) And they’ll spread via good, old-fashioned, in-person referrals from friends and coworkers.

“Oh, is that the book reader thing? I heard about that… How do you like it? Can I see it?”

And how many Kindle owners have you met who didn’t love it?

This isn’t a recipe for explosive growth. They’re not taking over or killing anything. And techies don’t need to care much for them to succeed. Engadget and Gizmodo can keep obsessing over tiny LCD devices and foldable Acer tablet concepts and are safe to completely ignore this market once it’s no longer shiny and novel. But there are a lot of people — including, significantly, most people over age 40 — who don’t like reading tiny text on bright LCD screens in devices loaded with distractions that die after 5 hours without their electric lifeline.

And this is one 27-year-old with 20/20 vision (for now) who also prefers it.

Most of Kottke’s problem with ebook readers can be solved in software:

But all these e-readers — the Kindle, Nook, Sony Reader, et al — are all focused on the wrong single use: books. (And in the case of at least the Nook and Kindle, the focus is on buying books from B&N and Amazon. The Kindle is more like a 7-Eleven than a book.) The correct single use is reading. Your device should make it equally easy to read books, magazine articles, newspapers, web sites, RSS feeds, PDFs, etc.

And I’ve already solved part of that. Despite making an iPhone app optimized for reading magazine-length text, I mostly read long content with my very beta Kindle-export feature (which sucks, and is about to be replaced with a much better version) because it’s so much more comfortable — the e-ink screen really is much easier on the eyes, and much more text fits on the Kindle’s screen than the iPhone’s. (If the rumor consensus is to be believed, the Apple tablet unicorn will only solve the latter problem.)

Writing off an entire category of devices because of easily improved software limitations is invalid and unwise. I love reading on my Kindle, and I hardly ever read books. I’ll do my part to make blog posts, online magazine articles, and news stories just as easy to read as books.

I don’t expect the ebook-reader market to be the next hot thing. But it’s also not a fad, and it’s not going away. These are great devices for reading, even if you need to use one before you’re convinced, and any objection to their current software limitations is likely to be temporary.

I’m not including RSS feeds or PDFs in the discussion. RSS feeds aren’t reading: they’re alerting, discovering and filtering. My preferred workflow, which Instapaper embodies, places RSS-inbox-clearing entirely before the reading step as its own process that’s always done with high speed using a native feed reader on a regular computer.

For a variety of technical and practical reasons, I don’t consider PDFs to be a good reading experience on any platform. It’s also not possible to universally transform them well, or even acceptably, to any screen smaller than their intended print size: letter-sized paper, usually. The Kindle DX comes close, but it’s a large, specialized device that’s not as well suited for the mass market as ebook readers with screens in the 6” range.

There’s also always going to be a subset of web and book content that doesn’t work well on ebook readers, such as content with a lot of tables, diagrams, photos, or embedded source code blocks. This matters to some, but lack of good support for this type of content won’t prevent the category from being generally successful.

https://marco.org/2009/10/27/cowsandmilk-asked-should-i-get-a-nook-for-my

cowsandmilk asked:

Should I get a Nook for my parents so they can change the font size? They’re both over 60 now and my dad reads with a magnifying glass.

I’ve found that the adjustable font size is the biggest selling point, by far, to older people.

I use the term “older” here loosely: older than me, the majority of the tech scene, and most of the people likely to be reading my blog. Old enough to regularly use magnifying glasses or raise the font sizes on web pages. In reality, this could mean as young as 40. But it certainly applies in larger numbers to people above 60.

A lot of people are buying Kindles for their parents or grandparents, primarily for the font-size adjustments. The anecdotes I’ve heard like this have all ended well with the recipient loving the Kindle.

(Given how similar they appear to be, I’m guessing the same will apply to the Nook. And I bet this will be a major selling point pushed by B&N salespeople while demoing the Nook to “older” people.)

https://marco.org/2009/10/28/world-of-goos-pay-what-you-want-report-has-some

World of Goo’s pay-what-you-want report has some great statistics about the average prices people paid. This one was surprising: I expected Windows users to be the cheapest, but I didn’t expect Linux users to be the most generous.

Anyway, if you haven’t played this ridiculously good game yet, go download the demo. If you like it, buy the full version ($20, direct download, DRM-free).

World of Goo is one of the best new games I’ve played this decade. Really. It’s that good.

https://marco.org/2009/10/29/one-handed-computing-with-the-iphone

Kottke points out the benefits and convenience of one-handed iPhone use.

Most of the time I’m using my iPhone, it’s one-handed. Left, specifically, as it comes from the left pocket. Instapaper was designed for all-left-handed operation because that’s how I use my phone most of the time: left fingers around the back to hold the right edge, left pinky holding up the bottom edge, and left thumb to hit buttons or rest on the top-left corner when not needed (usually when using tilt-scrolling) for extra grip.

(For what it’s worth, I’m right-handed.)

https://marco.org/2009/10/29/tiff-got-me-an-amazing-birthday-present-the

Tiff got me an amazing birthday* present: the 135mm f/2.0 L, the low-light medium-telephoto we’ve wished we had for many events, and widely regarded as the sharpest lens Canon makes.

I shot this hand-held from our bedroom window with it. This thing’s great. Obviously not a general-purpose lens (no prime at this length really could be), but definitely a lifesaver for when I need to shoot a musical performance in a bar, a wedding in a dim old church, or a speech in a darkened auditorium.

* My birthday’s in June, but this lens has been out of stock everywhere since the spring — until last week. It’s the only camera equipment I’ve wanted all year except February’s flashes, and it completes our lens collection for (probably) a long time.

https://marco.org/2009/10/30/the-rise-fall-of-the-nintendo-wii

When we first got the Wii a couple of years ago, it was a universal hit at Arc90. The bowling and golf games in the Wii sports package were just plain fun.

Fast forward about six months from the time we got the Wii and it’s a completely different story. It was hardly being used. Fast forward two years to today and I can confidently share that it probably hasn’t been turned on in over a year.

Every Wii owner I’ve spoken to, including myself, has the same story.

I’m not sure what could reasonably be done at this point to give the Wii better longevity and gameplay depth. Nearly every third-party title is awful. Nintendo’s games trickle out at a snail’s pace, and many of them are just as shallow, or more so, than Wii Sports.

One aspect that really doesn’t help is how dated the Wii’s graphics hardware is. It didn’t matter as much when the system was released in 2006 and everyone was (rightfully) enamored with the innovative new gameplay mechanics. But the Wii’s 480p resolution and Gamecube-era graphics hardware produce drab, dated, jagged-edged output on now-quite-affordable HDTVs, and it’s not helping the system age gracefully.

But the shallow, short-lived novelty of the few good Wii games is the truly fatal flaw. As this article states, it was a fad — and it ages as poorly as one. Playing Wii Sports today feels like reliving a shallow one-hit-wonder from the past, like listening to Kris Kross ironically in a PT Cruiser on your way home to feed your Tamagotchi and talk about Ron Paul on Reddit.

I’m not sure what Nintendo could do to convince the growing number of people tired with the Wii to come back to it. New sales were happening quickly enough that they didn’t need to care, but that’s now slowing. Where does the Wii go from here?

Like most used-up fads, I don’t think there’s a future for it.

I have no idea what Nintendo’s next console will look like, but I don’t think they have any great options. The novelty that made the Wii such a powerful fad will remove most people’s motivation to ever buy another system like it.

https://marco.org/2009/10/31/norml-judge-testifies-for-marijuana-legalization

NORML: Judge testifies for marijuana legalization in California.

Retired Orange County Superior Court Judge James P. Gray’s testimony was one of the last to be heard, and to use a World Series metaphor, we couldn’t have asked for a better “clean up” hitter.

(via dalasverdugo, optimisto, poortaste)